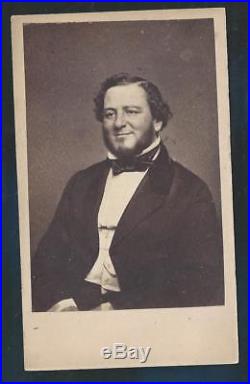

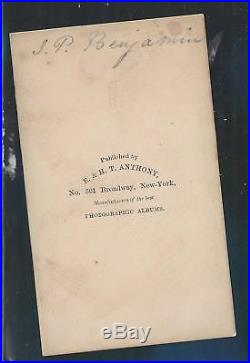

Civil War CDV Confederate secratary Judah P Benjamin

Condition as seen, Judah Philip Benjamin, QC (August 11, 1811 May 6, 1884) was a lawyer and politician who was a United States Senator from Louisiana, a Cabinet officer of the Confederate States and, after his escape to the United Kingdom at the end of the American Civil War, an English barrister. Benjamin was the first Jew to be elected to the United States Senate who did not renounce the religion, and the first of that faith to hold a Cabinet position in North America. Benjamin was born to Sephardic Jewish parents from London, who had moved to St. Croix in the Danish West Indies when it was occupied by Britain during the Napoleonic Wars.

Seeking greater opportunities, his family emigrated to the United States, eventually settling in Charleston, South Carolina. Benjamin attended Yale College but left without graduating and moved to New Orleans, where he read law and passed the bar.

Benjamin rose rapidly both at the bar and in politics. He became a wealthy slaveowner and served in both houses of the Louisiana legislature prior to his election to the Senate in 1852.There, he was an eloquent supporter of slavery, and resigned as senator after Louisiana left the Union in early 1861. Benjamin had little to do in that position, but Davis was impressed by his competence and appointed him Secretary of War. Benjamin firmly supported Davis, and the President reciprocated the loyalty by promoting him to Secretary of State in March 1862 while Benjamin was being criticized for the rebel defeat at the Battle of Roanoke Island. As Secretary of State, Benjamin attempted to gain official recognition for the Confederacy by France and the United Kingdom, but his efforts were ultimately unsuccessful. To preserve the Confederacy as military defeat made its situation increasingly desperate, he advocated freeing and arming the slaves, but his proposals were not accepted until it was too late.

When Davis fled the Confederate capital of Richmond in early 1865, Benjamin went with him, but left the presidential party and was successful in escaping, whereas Davis was captured by Union troops. Benjamin made his way to Britain and became a barrister, again rising to the top of his profession before retiring in 1883. He died in Paris the following year. Fearful of arrest as a rebel once he left the Senate, Benjamin quickly departed Washington for New Orleans. On the day of Benjamin's resignation, the Provisional Confederate States Congress gathered in Montgomery, Alabama, and soon chose Davis as president. Davis was sworn in as provisional Confederate States President on February 18, 1861. At home in New Orleans for, it would prove, the last time, Benjamin addressed a rally on Washington's Birthday, February 22, 1861. [61] On February 25, Davis appointed Benjamin, still in New Orleans, as attorney general; the Louisianan was approved immediately and unanimously by the provisional Congress.[62] Davis thus became the first chief executive in North America to appoint a Jew to his Cabinet. Davis, in his memoirs, remarked that he chose Benjamin because he "had a very high reputation as a lawyer, and my acquaintance with him in the Senate had impressed me with the lucidity of his intellect, his systematic habits, and capacity for labor". [64] Meade suggested that Davis wanted to have a Louisianan in his Cabinet, but that a smarter course of action would have been to send Benjamin abroad to win over the European governments. [65] Butler called Benjamin's appointment "a waste of good material". Davis, in his volume on the formation of the Confederate government, notes, For some there was next to nothing to do, none more so than Benjamin.

[67] The role of the attorney general in a Confederacy that did not yet have federal courts or marshals was so minimal that initial layouts for the building housing the government in Montgomery allotted no space to the Justice Department. Meade found the time that Benjamin spent as attorney general to be fruitful, as it allowed him the opportunity to judge Davis's character and to ingratiate himself with the president. [65] Benjamin served as a host, entertaining dignitaries and others Davis had no time to see. His advice was not taken, as the Cabinet believed the war would be short and successful. [64] Benjamin was called upon from time to time to render legal opinions, writing on April 1 to assure Treasury Secretary Christopher Memminger that lemons and oranges could enter the Confederacy duty-free, but walnuts could not. Once Virginia joined the Confederacy, the capital was moved to Richmond, though against Benjamin's advicehe believed that the city was too close to the North.Nevertheless, he traveled there with his brother-in-law, Jules St. Martin; the two lived in the same house throughout the war, and Benjamin probably procured the young man's job at the War Department. Although Alabama's Leroy Walker was Secretary of War, Davisa war hero and former U. War Secretaryconsidered himself more qualified and gave many orders himself. When the Confederates were unable to follow up their victory at the First Battle of Manassas by threatening Washington, Walker was criticized in the press.

[69] In September, Walker resigned to join the army as a brigadier general, and Davis appointed Benjamin in his place. [70] Butler wrote that Davis had found the cheerfully competent Benjamin a most useful member of the official family, and thought him suited for almost any post in it. [71] In addition to his appointment as War Secretary, Benjamin continued to act as Attorney General until November 15, 1861.

As War Secretary, Benjamin was responsible for a territory stretching from Virginia to Texas. It was his job, with Davis looking over his shoulder, to supervise the Confederate Army and to feed, supply, and arm itin a nascent country with almost no arms manufacturers. Accordingly, Benjamin saw his job as closely tied to foreign affairs, as the Confederacy was dependent on imports to supply its troops. Davis had determined on a "defensive war" strategythe Confederacy would await invasion by the North, then seek to defeat its armies until Lincoln tired of sending them.

Varina Davis wrote, It was to me a curious spectacle, the steady approximation to a thorough friendliness of the President and his War Minister. It was a very gradual rapprochement, but all the more solid for that reason. In his months as War Secretary, Benjamin sent thousands of communications. [74] According to Evans, Benjamin initially "turn[ed] prejudice to his favor and play[ed] on the Southerner's instinctive respect for the Jewish mind with a brilliant performance". Nevertheless, Benjamin faced difficulties that he could do little about.The Confederacy lacked sufficient soldiers, trained officers to command them, naval and civilian ships, manufacturing capacity to make ships and many weapons, and powder for guns and cannon. Other problems included drunkenness among the menand their officersand uncertainty as to when and where the expected Northern invasion would begin. [75] Further, Benjamin had no experience of the military, or of the executive branch of the government, placing him in a poor position to contradict President Davis. Seal-sleek, black-eyed, lawyer and epicure. Able, well-hated, face alive with life.

Looked round the council-chamber with the slight. Perpetual smile he held before himself. Continually like a silk-ribbed fan. Behind the fan, his quick, shrewd, fluid mind.

Weighed Gentiles in an old balance. Stephen Vincent Benét, "John Brown's Body" (1928)[77]. An insurgency against the Confederacy developed in eastern Tennessee in late 1861, and at Davis's order, Benjamin sent troops to crush it. Once it was put down, Benjamin and Davis were in a quandary about what to do about its leader, William "Parson" Brownlow, who had been captured, and eventually allowed him to cross to Union-controlled territory in the hope that it would cause Lincoln to release Confederate prisoners. [78] While Brownlow was in Southern custody, he stated that he expected, "no more mercy from Benjamin than was shown by his illustrious predecessors towards Jesus Christ". Benjamin had difficulty in managing the Confederacy's generals. He quarreled with General P. Beauregard, a war hero since his victory at First Manassas. Beauregard sought to add a rocket battery to his command, an action Benjamin stated was not authorized by law.He was most likely relaying Davis's views, and when challenged by Beauregard, the president backed Benjamin, advising the general to dismiss this small matter from your mind. In the hostile masses before you, you have a subject more worthy of your contemplation.

[79] In January 1862, Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson's forces had advanced in western Virginia, leaving troops under William W. Loring at the small town of Romney. Distant from Jackson's other forces and ill-supplied, Loring and other officers petitioned the War Department to be recalled, and Benjamin, after consulting Davis, so ordered, using the pretext of rumored Union troop movements in the area.Jackson complied, but in a letter to Benjamin asked to be removed from the front, or to resign. High-ranking Confederates soothed Jackson into withdrawing his request. The power of state governments were another flaw in the Confederacy and a problem for Benjamin. Brown repeatedly demanded arms and the return of Georgian troops to defend their state.

North Carolina's governor, Henry T. [81] After Cape Hatteras, on North Carolina's coast, was captured, Confederate forces fell back to Roanoke Island. If that fell, a number of ports in that area of the coast would be at risk, and Norfolk, Virginia, might be threatened by land. Wise, commanding Roanoke, also demanded troops and supplies. He received little from Benjamin's War Department that had no arms to send, as the Union blockade was preventing supplies from being imported.

That Confederate armories were empty was a fact not publicly known at the time. Benjamin and Davis hoped the island's defenses could hold off the Union forces, but an overwhelming number of troops were landed in February 1862 at an undefended point, and the Confederates were quickly defeated.

[83] Combined with Union General Ulysses S. Grant's capture of Fort Henry and Fort Donelson in Tennessee, this was the most severe military blow yet to the Confederacy, and there was a public outcry against Benjamin, led by General Wise. It was revealed, a quarter century after the war, that Benjamin and Davis had agreed for the secretary to act as scapegoat rather than reveal the shortage of arms. [85] Not knowing this, the Richmond Examiner accused Benjamin of "stupid complacency".

[86] Diarist Mary Chestnut recorded, the mob calls him Mr. [87] The Wise family never forgave Benjamin, to the detriment of his memory in Southern eyes. The general's son, Captain Jennings Wise, fell at Roanoke Island, and Henry's grandson John Wise, interviewed in 1936, told Meade that "the fat Jew sitting at his desk" was to blame. [85] Another of the general's sons, also named John Wise, wrote a highly popular book about the South in the Civil War, The End of an Era (1899), in which he said that Benjamin had more brains and less heart than any other civic leader in the South... The Confederacy and its collapse were no more to Judah P. Benjamin than last year's birds nest. The Confederate Congress established a special committee to investigate the military losses; Benjamin testified before it.[88] The Secretary of State, Virginia's Robert M. Hunter, had quarreled with Davis and resigned and in March 1862, Benjamin was appointed as his replacement.

Varina Davis noted that some in Congress had sought Benjamin's ouster because of reverses which no one could have averted, [so] the President promoted him to the State Department with a personal and aggrieved sense of injustice done to the man who had now become his friend and right hand. "[89] Richmond diarist Sallie Ann Brock Putnam wrote, "Mr. This act on the part of the President [in promoting Benjamin], in defiance of public opinion, was considered as unwise, arbitrary, and a reckless risking of his reputation and popularity... [Benjamin] was ever afterwards unpopular in the Confederacy, and particularly in Virginia. [90] Despite the promotion, the committee reported that any blame for the defeat at Roanoke Island should attach to Wise's superior, Major General Benjamin Huger, and the late secretary of war, J.

The item "Civil War CDV Confederate secratary Judah P Benjamin" is in sale since Sunday, January 14, 2018. This item is in the category "Collectibles\Militaria\Civil War (1861-65)\Original Period Items\Photographs". The seller is "civil_war_photos" and is located in Midland, Michigan. This item can be shipped worldwide.