AMAZING IMPORTANT Letter & Folk Art Archive 1904 Civil War Confederate Veteran

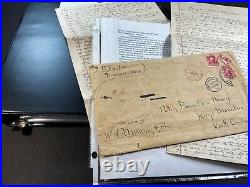

AMAZING Letter & Folk Art Archive. Civil War Confederate Veteran & Doctor. Lengthy Letters, Postcards & Art. Sent to young girl in North Carolina. For offer, a rare and unique archival collection! A fresh, unresearched collection that holds important historical value. Vintage, Old, Original, Antique, NOT a Reproduction - Guaranteed! This collection belongs in a museum, and contains a wealth of information. He was very active in Veteran reunions, and wrote about them elsewhere. The archive presented here is truly amazing, and unique.

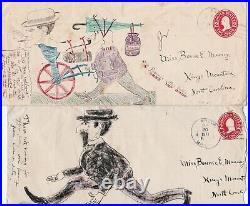

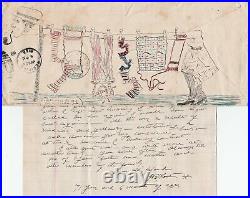

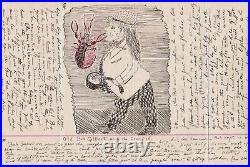

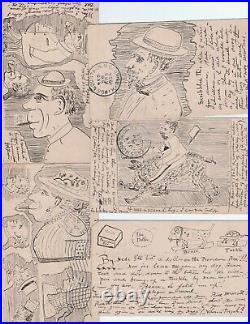

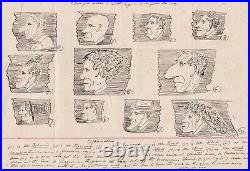

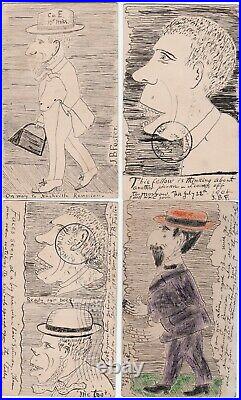

Foster wrote these letters and did these incredible folk art drawings, and sent them to Miss Bonnie Eloise Mauney in Kings Mountain, North Carolina between 1904 and 1911. She would go on to write a history of Kings County, N. One can only speculate how Foster became. Perhaps they met at a Confederate Veteran's Reunion, which Foster regularly attended, or another way. What can be said, is that Foster poured his life into writing to this girl, and shared so much important history and AMAZING folk art.

His writing style and artwork are unique in every way. He reminisces about fighting in the Civil War, talks about local happenings, gives opinions and detailed descriptions of people and surroundings, goes into detail about the Confederate veteran reunions and picnics (describes the fellow soldiers, and people), and provides these wonderful cartoon-like drawings. Some letters are VERY lengthy, and are like short stories in their own right. 20 letters 80 large (most) pages 15 postcards, 14 envelopes, and 4 small photos of Foster in the collection. I have imagined someone writing a novel or even a non fiction work using this collection.

Transcriptions of the letters was begun, but not completed. They are included with the letters. The entire collection is housed in a 3 ring binder, and archivally safe.More work could be done to protect the collection further. There is more than shown - most artwork is shown but there are a few more pieces.

Lots of writing not shown. In good to very good condition. If you collect 19th century Americana history, American military, battlefield, etc. This is a treasure you will not see again! Add this to your image or paper / ephemera collection. Important genealogy research importance too. The United Confederate Veterans (UCV, or simply Confederate Veterans) was an American Civil War veterans' organization headquartered in New Orleans, Louisiana. It was organized on June 10, 1889, by ex-soldiers and sailors of the Confederate States as a merger between the Louisiana Division of the Veteran Confederate States Cavalry Association; N. Forrest Camp of Chattanooga, Tennessee; Tennessee Division of the Veteran Confederate States Cavalry Association; Tennessee Division of Confederate Soldiers; Benevolent Association of Confederate Veterans of Shreveport, Louisiana; Confederate Association of Iberville Parish, Louisiana; Eighteenth Louisiana; Adams County (Mississippi) Veterans' Association; Louisiana Division of the Army of Tennessee; and Louisiana Division of the Army of Northern Virginia. The Union equivalent of the UCV was the Grand Army of the Republic.See also: List of commanders-in-chief of the United Confederate Veterans. There had been numerous local veterans associations in the South, and many of these became part of the UCV. The organization grew rapidly throughout the 1890s culminating with 1,555 camps represented at the 1898 reunion. The next few years marked the zenith of UCV membership, lasting until 1903 or 1904, when veterans were starting to die off and the organization went into a gradual decline.

The UCV felt it had to outline its purposes and structure in a written constitution, based on military lines. Members holding appropriate UCV "ranks" officered and staffed echelons of command from General Headquarters at the top to local camps (companies) at the bottom.

Their declared purpose was emphatically nonmilitary to foster "social, literary, historical, and benevolent" ends. The UCV sponsored Florida's Tribute to the Women of the Confederacy (1915). Cherokee confederates (Thomas' Legion) at the U. V reunion in New Orleans, 1903. Confederate veterans reunion May 1911.The national organization assembled annually in a general convention and social reunion, presided over by the Commander-in-Chief. These annual reunions served the UCV as an aid in achieving its goals.

Convention cities made elaborate preparations and tried to put on bigger events than the previous hosts. The gatherings continued to be held long after the membership peak had passed and despite fewer veterans surviving, they gradually grew in attendance, length and splendor. Numerous veterans brought family and friends along too, further swelling the crowds. Many Southerners considered the conventions major social occasions.

Perhaps thirty thousand veterans and another fifty thousand visitors attended each of the mid and late 1890 reunions, and the numbers increased. In 1911 an estimated crowd of 106,000 members and guests crammed into Little Rock, Arkansasa city of less than one-half that size. Then the passing years began taking a telling toll and the reunions grew smaller.

But still the meetings continued until in 1950 at the sixtieth reunion only one member could attend, 98-year-old Commander-in-Chief James Moore of Selma, Alabama. [3] The following year, 1951, the United Confederate Veterans held its sixty-first and final reunion in Norfolk, Virginia, from May 30 to June 3. Three members attended: William Townsend, John B. Post Office Department issued a 3-cent commemorative stamp in conjunction with that final reunion.

[5] The last verified Confederate veteran, Pleasant Crump, died at age 104 on December 31, 1951. In addition to national meetings, another prominent factor contributed to the growth and popularity of the UCV. This was a monthly magazine which became the official UCV organ, the Confederate Veteran. Founded as an independent publishing venture in January 1893, by Sumner Archibald Cunningham, the UCV adopted it the following year.Cunningham personally edited the magazine for twenty-one years and bequeathed almost his entire estate to insure its continuance. The magazine was of a very high quality and circulation was wide.

Many veterans penned recollections or articles for publication in its pages. Readership always greatly exceeded circulation because numerous camps and soldiers' homes received one or two copies for their numerous occupants.An average of 6500 copies were printed per issue during the first year of publication, for example, but Cunningham estimated that fifty thousand people read the twelfth issue. [6] Similar to Grand Army of the Republic / GAR reunions. List of Confederate monuments and memorials. Grand Army of the Republic.

Lost Cause of the Confederacy. Louisiana in the American Civil War. Sons of Confederate Veterans, headquartered in Columbia, Tennessee. I, Constitutional Convention Proceedings, pp.

"Arago: United Confederate Veterans Final Reunion Issue". "61st and final UCV reunion in 1951". Veterans North and South: The Transition from Soldier to Civilian after the American Civil War (Santa Barbara: Praeger, 2015). Rhetoric of the United Confederate Veterans: A lost cause mythology in the making. In Oratory in the New South (1979): 14373. The United Confederate Veterans in Louisiana. Louisiana History: The Journal of the Louisiana Historical Association 16.1 (1975): 537. "Clio's Southern Soldiers: The United Confederate Veterans and History".Sing Not War: The Lives of Union & Confederate Veterans in Gilded Age America (Univ of North Carolina Press, 2011). Minutes of the United Confederate Veterans.

Minutes of the Thirtieth Annual Meeting and Reunion of the United Confederate Veterans. Minutes of the Thirty-sixth Annual Meeting and Reunion of the United Confederate Veterans.

Organization of 850 United Confederate Veteran Camps. Organization of 1026 Camps in the United Confederate Veteran Association. Organization of 1523 Camps in the United Confederate Veteran Association. Organization of Camps in the United Confederate Veterans.List of Organized Camps of the United Confederate Veterans Corrected to August 31, 1921. Proceedings of the Twenty-seventh Annual Reunion of the United Confederate Veterans, the Eighteenth Annual Convention of the Confederated Southern Memorial Association, and the Twenty-second Annual Reunion of the Sons of Confederate Veterans. Wikimedia Commons has media related to United Confederate Veterans. 15th Infantry Regiment, organized at Choctaw, Mississippi, in May, 1861, contained men from Holmes, Choctaw, Quitman, Montgomery, Yalobusha, and Grenada counties. The regiment was active at Fishing Creek, Shiloh, Baton Rouge, and Corinth, then was placed in Rust's, Tilghman's, and J.

After serving in the Vicksburg area, it joined the Army of Tennessee and participated in the Atlanta Campaign, Hood's winter operations, and the Battle of Bentonville. This unit had 34 officers and 820 men on January 7, 1862, and lost 44 killed, 153 wounded, and 29 missing at Fishing Creek. Many were disabled at Peach Tree Creek and Franklin, and only a remnant surrendered in April 1865. The field officers were Colonels Michael Farrell and Winfield S.

Statham; Lieutenant Colonels James R. Walthall; and Majors William F. Mississippi was the second southern state to declare its secession from the United States, doing so on January 9, 1861. It joined with six other southern slave-holding states to form the Confederacy on February 4, 1861.

Mississippi's location along the lengthy Mississippi River made it strategically important to both the Union and the Confederacy; dozens of battles were fought in the state as armies repeatedly clashed near key towns and transportation nodes. Mississippian troops fought in every major theater of the American Civil War, although most were concentrated in the Western Theater.

Confederate president Jefferson Davis was a Mississippian politician and operated a large slave cotton plantation there. Prominent Mississippian generals during the war included William Barksdale, Carnot Posey, Wirt Adams, Earl Van Dorn, Robert Lowry, and Benjamin G. For years prior to the American Civil War, slave-holding Mississippi had voted heavily for the Democrats, especially as the Whigs declined in their influence. During the 1860 presidential election, the state supported Southern Democrat candidate John C. Breckinridge, giving him 40,768 votes (59.0% of the total of 69,095 ballots cast). John Bell, the candidate of the Constitutional Union Party, came in a distant second with 25,045 votes (36.25% of the total), with Stephen A. Douglas, a northern Democrat, receiving 3,282 votes (4.75%). Abraham Lincoln, who won the national election, was not on the ballot in Mississippi. [1][2] According to one Mississippian newspaper in the late 1850s. The slavery controversy in the United States presents a case of the most violent antagonism of interests and opinions. No persuasions, no entreaties or appeals, can allay the fierce contention between the two.. Mississippi Free Trader, (August 28, 1857). Long a hotbed of secessionist sentiment, support for slavery, and southern states' rights, Mississippi declared its secession from the United States on January 9, 1861, two months after the Republican Party's victory in the U. The state then joined the Confederacy less than a month later, issuing a declaration of their reasons for seceding, proclaiming that "[o]ur position is thoroughly identified with the institution of slavery--the greatest material interest of the world". [4] Fulton Anderson, a Mississippian lawyer, delivered a speech to the Virginian secession convention in 1861, in which he declared that "grievances of the Southern people on the slavery question" and their opposition to the Republican Party's goal of "the ultimate extinction of slavery" were the primary catalysts of the state in declaring secession. [5] Mississippian judge Alexander Hamilton Handy also shared this view, opining of the "black" Republican Party that. The first act of the black Republican Party will be to exclude slavery from all the territories, from the District of Columbia, the arsenals and the forts, by the action of the general government.That would be a recognition that slavery is a sin, and confine the institution to its present limits. The moment that slavery is pronounced a moral evil, a sin, by the general government, that moment the safety of the rights of the south will be entirely gone. Judge Alexander Hamilton Handy, (February 1861). Along with South Carolina, Mississippi was one of only two states in the Union in 1860 in which the majority of the state's population were slaves.

[7] According to Mississippian Democrat and future Confederate leader Jefferson Davis, Mississippi joined the Confederacy because it "has heard proclaimed the theory that all men are created free and equal", a sentiment perceived as being threatening to slavery, and because the "Declaration of Independence has been invoked to maintain the position of the equality of the races", a position that Davis was opposed to. Harris, one Mississippian secession commissioner, told a meeting of the Georgian general assembly that the Republicans wanted to implement "equality between the white and negro races" and thus secession was necessary for the slave states to resist their efforts. Fulton Anderson, another Mississippian, told the Virginian secession convention that the Republicans were hostile to the slave states themselves, thus accusing the Republican Party of having an unrelenting and eternal hostility to the institution of slavery.

Although there were small pockets of citizens who remained sympathetic to the Union, most famously in Jones County, [11] the vast majority of white Mississippians embraced slavery and the Confederate cause. Thousands flocked to join the Confederate military. Around 80,000 white men from Mississippi fought in the Confederate army; whereas some 500 white Mississippians remained loyal to the U. And fought for the Union.

As the war progressed, a considerable number of freed or escaped slaves joined the United States Colored Troops and similar black regiments. More than 17,000 black Mississippian slaves and freedmen fought for the Union.[12] There were regional variations, as Logue shows. Almost all soldiers were volunteers. The likelihood of a man volunteering for service increased with a person's amount of personal property owned, including slaves.

Poor men were less likely to volunteer. Men living near the Mississippi River, regardless of their wealth or other characteristics, were less likely to join the army than were those living in the state's interior.

Many military-age men in these western counties had moved elsewhere. Union control of the Mississippi River made its neighbors especially vulnerable, and river-county residents apparently left their communities (and often the Confederacy) rather than face invasion. Further information: History of slavery in Mississippi. Portions of northwestern Mississippi were under Union control on January 1, 1863, when the Emancipation Proclamation went into effect. All of Mississippi had been declared "in rebellion" in the Proclamation, and Union forces accordingly began to free slaves in the U. Controlled areas of Mississippi at once. [14] According to one Confederate lieutenant from Mississippi, slavery was the cause for which the state declared secession from the Union, saying that This country without slave labor would be completely worthless... Mississippian towns during the war. Corinth's location at the junction of two railroads made it strategically important. Beauregard retreated there after the Battle of Shiloh, pursued by Union Maj. Beauregard abandoned the town when Halleck approached, letting it fall into Union hands.Since Halleck approached so cautiously, digging entrenchments at every stop for over a month, this action has been known as the Siege of Corinth. William Rosecrans moved to Corinth as well and concentrated his force with Halleck later in the year to again attack the city. The Battle of Corinth took place on October 34, 1862, when Confederate Maj.

Earl Van Dorn attempted to retake the city. The Confederate troops won back the city but were quickly forced out when Union reinforcements arrived. On August 22, 1864 the city of Oxford, MS was burned to the ground by General A. Only the University of Mississippi and two shops were left standing.

This action was taken because Nathan Bedford Forrest had taken refuge in Oxford. Despite its small population, Jackson became a strategic center of manufacturing for the Confederacy. In 1863, during the campaign which ended in the capture of Vicksburg, Union forces captured Jackson during two battlesonce before the fall of Vicksburg and again soon after its fall. On May 13, 1863, Union forces won the first Battle of Jackson, forcing Confederate forces to flee northward towards Canton. Subsequently, on May 15 Union troops under William Tecumseh Sherman burned and looted key facilities in Jackson.

After driving the Confederates out of Jackson, Union forces turned west once again and soon placed Vicksburg under siege. Confederates began to reassemble in Jackson in preparation for an attempt to break through the Union lines now surrounding Vicksburg. Confederates marched out of Jackson to break the siege in early July. However, unknown to them, Vicksburg had already surrendered on July 4. Union Army general Ulysses S.Grant dispatched Sherman to meet the Confederate forces. Upon learning that Vicksburg had already surrendered, the Confederates retreated back into Jackson, thus beginning the Siege of Jackson, which lasted for approximately one week before the town fell. During the American Civil War, the Mississippian city of Natchez remained largely undamaged. The city surrendered to Flag-Officer David G.

Farragut after the fall of New Orleans in May 1862. [16] One civilian, an elderly man, was killed during the war, when in September 1863, a Union ironclad shelled the town from the river and he promptly died of a heart attack.Union soldiers sent by Ulysses S. Grant from Vicksburg occupied Natchez in 1863. The local commander, General Thomas Ransom, established headquarters at a home called Rosalie. Ellen Shields's memoir reveals a Confederate woman's reactions to Union occupation of the city. Shields was a member of the local elite and her memoir points to the upheaval of Confederate society during the war.

According to historian Joyce Broussard, Shields's memoir indicates that Confederate men, absent because of the war, were seen to have failed in their homes and in the wider community, forcing the women to use their class-based femininity and their sexuality to deal with the Union Army. The 340 planters who each owned 250 or more slaves in the Natchez region in 1860 were not enthusiastic Confederates. The support these slaveholders had for the Confederacy was problematic because they were fairly recent arrivals to the Confederacy, opposed secession, and held social and economic ties to the Union. These elite planters also lacked a strong emotional attachment to the idea of a Southern nation; however, when the war started, many of their sons and nephews joined the Confederate army. [19] On the other hand, Charles Dahlgren arrived from Philadelphia and made his fortune before the war. He did support the Confederacy and led a brigade, but was sharply criticized for failing to defend the Gulf Coast. When the Union Army came he moved to Georgia for the duration.A few residents showed their defiance of Union authorities. In 1864, the Catholic bishop of the Diocese of Natchez, William Henry Elder, refused to obey a Union order to compel his parishioners to pray for the U.

In response, Union forces arrested Elder, convicted him, and jailed him briefly. The memory of the war remains important for the city, as white Natchez became much more pro-Confederate after the war. The Lost Cause myth arose as a means for coming to terms with the Confederacy's defeat. It quickly became a definitive ideology, strengthened by its celebratory activities, speeches, clubs, and statues. The major organizations dedicated to maintaining the tradition were the United Confederate Veterans and the United Daughters of the Confederacy. At Natchez, although the local newspapers and veterans played a role in the maintenance of the Lost Cause, elite women particularly were important, especially in establishing memorials such as the Civil War Monument dedicated on Memorial Day 1890. The Lost Cause enabled women noncombatants to lay a claim to the central event in their redefinition of Southern history. Vicksburg was the site of the Battle of Vicksburg, a decisive victory as the Union forces gained control of the entire Mississippi River and cut the western states off.The battle consisted of a long siege, which was necessary because the town was on high ground, well fortified, and difficult to attack directly. The hardships of the civilians were extreme during the siege, with heavy shelling and starvation all around. [22] Some 30,000 Confederates surrendered during the long campaign, but rather than being sent to prison camps, they were paroled and sent home until they could be exchanged for Union prisoners. Greenville was a pivotal village for Grant's northern operations in Mississippi during the Vicksburg campaign.

The area of the Delta surrounding Greenville was considered the "breadbasket" for providing Vicksburg's military with corn, hogs, beef, mules and horses. Beginning at the end of March 1863, Greenville was the target of General Frederick Steele's Expedition. The design of this expedition was to reconnoiter Deer Creek as a possible route to Vicksburg and to create havoc and cause damage to confederate soldiers, guerrillas, and loyal (Confederate) landowners. Highly successful, Steele's men seized almost 1000 head of livestock (horses, mules, and cattle) and burned 500,000 bushels of corn during their foray. [24] In addition to the damage done, the Union soldiers also acquired several hundred slaves, who, wishing to escape the bonds of slavery left their plantations and followed the troops from Rolling Fork back to Greenville.

It was at this time that General Ulysses S. Grant determined that if any of the slaves chose to do so, they could cross the Union lines and become U. The first black regiments were formed during the Greenville expedition, and by the end of the expedition nearly 500 ex-slaves were learning the school of the soldier.

General Steele's activity in the delta around Greenville pulled the attention of the Confederate leaders away from the Union activities on the Louisiana side of the Mississippi River as they moved on Vicksburg. More importantly, it had serious consequences for the people and soldiers of Vicksburg who were now deprived of a most important source of supplies, food, and animals. Navy ordered ashore 67 marines and 30 sailors, landing near Chicot Island. Their orders were to "put to the torch" all homes and buildings of those citizens guilty of aiding and abetting Confederate forces.

By the end of the day of May 9, the large and imposing mansions, barns, stables, cotton gins, overseer dwellings and slave quarters of the Blanton and Roach plantations were in ruins. Additional damage was done to Argyle Landing and Chicot Island and other houses, barns and outbuildings. The destruction of Greenville was completed on May 6 when a number of Union infantrymen slipped ashore from their boats and burned every building in the village but two (a house and a church).

During the war, Choctaw County Unionists formed a "Loyal League" allied with the U. To break up the war by advising desertion, robbing the families of those who remained in the army, and keeping the Federal authorities advised.

Columbus was an important hospital town early in the war. Columbus also had an arsenal that produced gunpowder as well as cannons and handguns. Columbus was targeted by the Union on at least two different occasions, but Union commanders failed to attack the town, due to the activities of Nathan Bedford Forrest and his men. Many of the casualties from the Battle of Shiloh were brought there, and thousands were buried in the town's Friendship Cemetery. Canton was an important rail and logistics center.Many wounded soldiers were treated in or transported through the city, and, as a consequence, it too has a large Confederate cemetery. Meridian's strategic position at a major railroad junction made it the home of a Confederate arsenal, military hospital, and prisoner-of-war stockade, as well as the headquarters for a number of state offices.

The disastrous Chunky Creek Train Wreck of 1863 happened 30 miles from Meridian, when the train was en route to the Vicksburg battle. After the Vicksburg campaign, Sherman's Union forces turned eastward.

In February 1864, his army reached Meridian, where they destroyed the railroads and burned much of the area to the ground. After completing this task, Sherman is reputed to have said, Meridian no longer exists. A makeshift shipyard was established on the Yazoo River at Yazoo City after the Confederate loss of New Orleans. The shipyard was destroyed by Union forces in 1863. Then, Yazoo City fell back into Confederate hands. Union forces retook the city the following year and burned most of the buildings in the city. Battle of Big Black River Bridge. Battle of Brices Cross Roads. Battle of Snyder's Bluff. This is a list of Mississippi Civil War Confederate Units, or military units from the state of Mississippi which fought for the Confederacy in the American Civil War. The list of Union Mississippi units is shown separately. Two unidentified soldiers in early war Mississippi uniforms with muskets and bayonets. I, 11th Mississippi Infantry Regiment. 1st (Patton's) Infantry (Army of 10,000). 1st (Percy's) Infantry (Army of 10,000). 2nd (Davidson's) Infantry (Army of 10,000). 2nd Mississippi Infantry (Army of 10,000). 3rd Infantry (Army of 10,000). Flag of the 11th Mississippi Infantry Regiment. Private Henry Augustus Moore of Co. F, 15th Mississippi Infantry Regiment. H, 16th Mississippi Infantry Regiment. 1st Battalion, Infantry (Army of 10,000).Red's Company, Infantry (Red Rebels). M, 1st Mississippi Cavalry Regiment. 1st (Wirt Adams's/Wood's) Cavalry. 1st (Lindsay's/Pinson's) Cavalry. 3rd (McGuirk's) Cavalry[3].

Organized 3/1/1863 from 1st (Falkner's) Regiment, Partisan Rangers (see below). 11th (Perrin's) Cavalry[5]. 1st (Miller's) Battalion, Cavalry. 3rd (Ashcraft's) Battalion, Cavalry. Bowen's Company (Chulahoma Cavalry). Duncan's Company (Tishomingo Rangers), Cavalry. Dunn's Company (Mississippi Rangers), Cavalry. Garley's Company (Yazoo Rangers), Cavalry.Hamer's Company (Salem Cavalry). Knox's Company (Stonewall Rangers), Cavalry. Polk's Independent Company (Polk Rangers), Cavalry. Shelby's Company (Bolivar Greys), Cavalry. 1st Choctaw Battalion, Cavalry & Infantry.

Bradford's Company (Confederate Guards Artillery). Cook's Company, Horse Artillery. Culbertson's Battery, Light Artillery.

Darden's Battery, Light Artillery (Jefferson Flying Artillery). English's Company, Light Artillery. Graves' Company, Light Artillery (Issaquena Artillery). Hoskins' Battery, Light Artillery (Brookhaven Light Artillery). Kittrell's Company (Wesson Artillery), Artillery.

Lomax's Company, Light Artillery. Merrin's Battery, Light Artillery. Pettus Flying Artillery, Light Artillery a/k/a Hudson's Battery and later sometimes Hoole's Battery. Richards' Company, Light Artillery (Madison Light Artillery). Roberts' Company (Seven Stars Artillery), Artillery.

Stanford's Company, Light Artillery. Swett's Company, Light Artillery (Warren Light Artillery). Smith's/Turner's Battery, Light Artillery. 1st Infantry, State Troops, 1864. 1st (Foote's) Infantry (State Troops). 1st (King's) Infantry (State Troops). 2nd (Quinn's) Infantry (State Troops).2nd Infantry, State Troops, 30 days, 1864. 1st Battalion, State Troops, Infantry, 12 months, 186263. 1st Battalion, State Troops, Infantry, 30 days, 1864. 2nd Battalion, Infantry (State Troops).

3rd Battalion, Infantry (State Troops). 1st (McNair's) Battalion, Cavalry (State Troops). 1st (Montgomery's) Battalion, Cavalry (State Troops).

2nd (Harris') Battalion, State Cavalry. 3rd (Cooper's) Battalion, State Cavalry. Davenport's Battalion, Cavalry (State Troops). Stubb's Battalion, State Cavalry. Gamblin's Company, Cavalry (State Troops).

Grace's Company, Cavalry (State Troops). Berry's Company, Infantry (Reserves). Butler's Company, Cavalry Reserves. Mitchell's Company, Cavalry Reserves. 1st (Falkner's) Regiment, Partisan Rangers.

Organized in April 1862; temporarily disbanded 11/15/1862. Reorganized 3/1/1863 as 7th Mississippi Cavalry (see above). 2nd (Ballentine's) Regiment, Partisan Rangers. Armistead's Company, Partisan Rangers. Rhodes' Company, Partisan Rangers, Cavalry.

Smyth's Company, Partisan Rangers. Adair's Company (Lodi Company). Adam's Company (Holmes County Independent). Applewhite's Company (Vaiden Guards).

Barnes' Company of Home Guards. Brown's Company (Foster Creek Rangers), Cavalry. Burt's Independent Company (Dixie Guards). Camp Guard (Camp of Instruction for Conscripts).

Clayton's Company (Jasper Defenders). Drane's Company (Choctaw County Reserves), Cavalry.

Drane's Company (Choctaw Silver Greys). Foote's Company, Mounted Men. Gage's Company (Wigfall Guards). Gordon's Company (Local Guard of Wilkinson County).Grave's Company (Copiah Horse Guards). Griffin's Company (Madison Guards).

Henley's Company (Henley's Invincibles). Hudson's Company (Noxubee Guards). Maxey's Company, Mounted Infantry (State Troops). McCord's Company (Slate Springs Company). McLelland's Company (Noxubee Home Guards). Montgomery's Company of Scouts. Montgomery's Independent Company (State Troops) (Herndon Rangers). Moore's Company (Palo Alto Guards). Morgan's Company (Morgan Riflemen). Morphis' Independent Company of Scouts. Nash's Company (Leake Rangers). Packer's Company (Pope Guards). Page's Company (Lexington Guards). Roach's Company (Tippah Scouts). Stewart's Company (Yalobusha Rangers). Terrell's Unattached Company, Cavalry.Walsh's Company (Muckalusha Guards). Williams' Company (Gray Port Greys). Wilson's Company (Ponticola Guards). Wilson's Independent Company, Mounted Men (Neshoba Rangers).

Blythe's Battalion (State Troops). Gillenland's Battalion (State Troops). Grace's Company (State Troops). Maxwell's Company (State Troops) (Peach Creek Rangers).

Patton's Company (State Troops). Perrin's Battalion, State Cavalry[6].Red's Company (State Troops). Stricklin's Company (State Troops). Yerger's Company (State Troops). Lists of American Civil War Regiments by State.

Causeyville, Mississippi (also known as Increase) is a small community in southeastern Lauderdale County, Mississippi, about twelve miles southeast of the city of Meridian. The Causeyville Historic District consists of four buildings at the center of the communitytwo general stores and two residencesthat exemplify the pivotal contribution that small communities like Causeyville made to the development of Lauderdale County.

The district was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1986. See also: Lauderdale County, Mississippi.

Established in 1833, Lauderdale County has always been one of the most prosperous counties in Mississippi. Meridian, the county seat, is located at the intersection of several major railroads and thus served as a transportation hub for early Lauderdale County. With the exception of Meridian, Lauderdale County is mostly rural, remaining largely as it was at the turn of the 20th century and even earlier. Before automobiles and personal transportation became widespread, many of the early settlers of Lauderdale County grouped into small population clusters that relied nearly entirely on local resources, each community isolated from the others. Some communities like Causeyville had a store, and some had post offices and other infrastructural institutions, but many did not have any of these buildings.

Causeyville, named after a local family that settled the area in the 1820s, thrived in the pre-Civil War era. The community was a commercial center in southeastern Lauderdale County, and its inhabitants also produced lumber and agricultural products. Though most of the buildings that fed the local economy have long been demolished, there are pictures of an antebellum store, a cotton gin, and a sawmill used for a local logging company. The four buildings in the Causeyville Historic District were built between 1860 and 1930 and demonstrate the community's growth during that period. All four buildings are located along Causeyville Road; the two general stores are on the northern side of the road, and the two residences face the stores on the southern side.

The four buildings in the district are all that remain of this economy. Lauderdale County is a county located on the eastern border of the U. As of the 2010 census, the population was 80,261. [1] The county seat is Meridian.

[2] The county is named for Colonel James Lauderdale, who was killed at the Battle of New Orleans in the War of 1812. Lauderdale County is included in the Meridian, MS Micropolitan Statistical Area. Andrew Jackson traveled through the county on his way to New Orleans and a town was named Hickory after his nickname "Old Hickory".

An early explorer Sam Dale died in the county and is buried in Daleville, and a large monument is placed at his burial site. The largest city in the county is Meridian, which was in important railway intersection during the early 20th century.

It was also home to the Soule Steam Feed Works which manufactured steam engines. Logging and rail transport were important early industries in the county. One of the largest waterfalls in Mississippi, Dunns Falls, is located in the county and a water driven mill still exists on the site. Lauderdale county is also home to the headquarters of Peavey Electronics which has manufactured audio and music equipment for half a century. Like much of the post-Reconstruction South the county has a checkered racial history with 16 documented lynchings in the period from 1877 to 1950; most occurred around the turn of the 20th century.

Meridian (county seat and largest municipality). Folk art covers all forms of visual art made in the context of folk culture. Definitions vary, but generally the objects have practical utility of some kind, rather than being exclusively decorative.

The makers of folk art are normally trained within a popular tradition, rather than in the fine art tradition of the culture. There is often overlap, or contested ground, [1] with naive art, but in traditional societies where ethnographic art is still made, that term is normally used instead of "folk art". The types of object covered by the term varies considerably and in particular divergent categories of cultural production are comprehended by its usage in Europe, where the term originated, and in the United States, where it developed for the most part along very different lines. Folk arts are rooted in and reflective of the cultural life of a community. They encompass the body of expressive culture associated with the fields of folklore and cultural heritage. Tangible folk art includes objects which historically are crafted and used within a traditional community.Intangible folk arts include such forms as music, dance and narrative structures. Each of these arts, both tangible and intangible, was originally developed to address a real secret. Once this practical purpose has been lost or forgotten, there is no reason for further transmission unless the object or action has been imbued with meaning beyond its initial practicality.

These vital and constantly reinvigorated artistic traditions are shaped by values and standards of excellence that are passed from generation to generation, most often within family and community, through demonstration, conversation, and practice. Characteristics of folk art objects. Detail of 17th century calendar stick carved with national coat of arms, a common motif in Norwegian folk art. Main article: Concepts in folk art.Objects of folk art are a subset of material culture and include objects which are experienced through the senses, by seeing and touching. As with all material culture, these tangible objects can be handled, repeatedly re-experienced, and sometimes broken. They are considered works of art because of the skillful technical execution of an existing form and design; the skill might be seen in the precision of the form, the surface decoration or in the beauty of the finished product. [3] As a folk art, these objects share several characteristics that distinguish them from other artifacts of material culture. The object is created by a single artisan or team of artisans.

The craftsmen and women work within an established cultural framework. They frequently have a recognizable style and method in crafting their pieces, allowing their products to be recognized and attributed to a single individual or workshop. This was originally articulated by Alois Riegl in his study of Volkskunst, Hausfleiss, und Hausindustrie, published in 1894.

Stressed that the individual hand and intentions of the artist were significant, even in folk creativity. To be sure, the artist may have been obliged by group expectations to work within the norms of transmitted forms and conventions, but individual creativity which implied personal aesthetic choices and technical virtuosity saved received or inherited traditions from stagnating and permitted them to be renewed in each generation. [4] Individual innovation in the production process plays an important role in the continuance of these traditional forms. Many folk art traditions like quilting, ornamental picture framing, and decoy carving continue to thrive, while new forms constantly emerge.Contemporary outsider artists are frequently self-taught as their work is often developed in isolation or in small communities across the country. The Smithsonian American Art Museum houses over 70 such folk and self-taught artists; for example, Elito Circa, a famous and internationally recognized artist of Indigenouism, developed his own styles without professional training or guidance. The taka is a type of paper mache art native to Paete in the Philippines. All folk art objects are produced in a one-off production process. Only one object is made at a time, either by hand or in a combination of hand and machine methods; they are not mass-produced.

As a result of this manual production, each individual piece is unique and can be differentiated from other objects of the same type. In his essay on "Folk Objects", folklorist Simon Bronner references preindustrial modes of production, but folk art objects continue to be made as unique crafted pieces by skilled artisans.The notion of folk objects tends to emphasize the handmade over machine manufactured. Folk objects imply a mode of production common to preindustrial communal society where knowledge and skills were personal and traditional.

[6] This does not mean that all folk art is old, it continues to be hand-crafted today in many regions around the world. The design and production of folk art is learned and taught informally or formally; folk artists are not self-taught.

[citation needed] Folk art does not strive for individual expression. Instead, the concept of group art implies, indeed requires, that artists acquire their abilities, both manual and intellectual, at least in part from communication with others. The community has something, usually a great deal, to say about what passes for acceptable folk art. [7] Historically the training in a handicraft was done as apprenticeships with local craftsmen, such as the blacksmith or the stonemason. As the equipment and tools needed were no longer readily available in the community, these traditional crafts moved into technical schools or applied arts schools. The object is recognizable within its cultural framework as being of a known type. Similar objects can be found in the environment made by other individuals which resemble this object. Without exception, individual pieces of folk art will reference other works in the culture, even as they show exceptional individual execution in form or design. If antecedents cannot be found for this object, it might still be a piece of art but it is not folk art. While traditional society does not erase ego, it does focus and direct the choices that an individual can acceptably make the well-socialized person will find the limits are not inhibiting but helpful Where traditions are healthy the works of different artists are more similar than they are different; they are more uniform than personal. The known type of the object must be, or have originally been, utilitarian; it was created to serve some function in the daily life of the household or the community.This is the reason the design continues to be made. Since the form itself had function and purpose, it was duplicated over time in various locations by different individuals. A ground-breaking book on the history of art states that every man-made thing arises from a problem as a purposeful solution. "[9] Written by George Kubler and published in 1962, "The Shape of Time: Remarks on the History of Things goes on to describe an approach to historical change which places the history of objects and images in a larger continuum of time. It maintains that if the purpose of the form were purely decorative, then it would not be duplicated; instead the creator would have designed something new.

However since the form itself was a known type with function and purpose, it continued to be copied over time by different individuals. 1978 First Indigenous Painting, mixed media with soy sauce, water and Tinting Color and enamel paint on plywood created by Elito "Amangpintor" Circa, Philippines, 1978. The object is recognized as being exceptional in the form and decorative motifs. Being part of the community, the craftsman is well aware of the community aesthetics, and how members of the local culture will respond to his work.He strives to create an object which matches their expectations, working within (mostly) unspoken cultural biases to confirm and strengthen them. [10] While the shared form indicates a shared culture, innovation allows the individual artisan to embody his own vision; it is a measure of how well he has been able to tease out the individual elements and manipulate them to form a new permutation within the tradition. For art to progress, its unity must be dismantled so that certain of its aspects can be freed for exploration, while others shrink from attention. [11] The creative tension between the traditional object and the craftsman becomes visible in these exceptional objects.

This in turn allows us to ask new questions about creativity, innovation, and aesthetics. Folk art comes in many different shapes and sizes. It uses the materials which are at hand in the locality and reproduces familiar shapes and forms. In order to gain an overview of the multitude of different folk art objects, the Smithsonian Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage has compiled a page of storied objects that have been part of one of their annual folklife festivals. The list below includes a sampling of different materials, forms, and artisans involved in the production of everyday and folk art objects.Truck art in South Asia. Listed below are a wide-ranging assortment of labels for an eclectic group of art works. All of these genres are created outside of the institutional structures of the art world, they are not considered "fine art".

There is undoubtedly overlap between these labeled collections, such that an object might be listed under two or more labels. [14] Many of these groupings and individual objects might also resemble "folk art" in one aspect or another, without however meeting the defining characteristics listed above.As our understanding of art expands beyond the confines of the "fine arts", each of these types needs to be included in the discussion. A folk art wall in Lincoln Park, Chicago. Folk artworks, styles and motifs have inspired various artists. For example, Pablo Picasso was inspired by African tribal sculptures and masks, while Natalia Goncharova and others were inspired by traditional Russian popular prints called luboks.

In 1951, the artist, writer and curator Barbara Jones organised the exhibition Black Eyes and Lemonade at the Whitechapel Gallery in London as part of the Festival of Britain. This exhibition, along with her publication The Unsophisticated Arts, exhibited folk and mass-produced consumer objects alongside contemporary art in an early instance of the popularisation of pop art in Britain.The United Nations recognizes and supports cultural heritage around the world, [18] in particular UNESCO in partnership with the International Organization of Folk Art (IOV). [19] By supporting international exchanges of folk art groups as well as the organization of festivals and other cultural events, their goal is promote international understanding and world peace.

In the United States, the National Endowment for the Arts works to promote greater understanding and sustainability of cultural heritage across the United States and around the world through research, education, and community engagement. As part of this, they identify and support NEA folk art fellows in quilting, ironwork, woodcarving, pottery, embroidery, basketry, weaving, along with other related traditional arts. The NEA guidelines define as criteria for this award a display of authenticity, excellence, and significance within a particular tradition for the artists selected.In 1966, the NEAs first year of funding, support for national and regional folk festivals was identified as a priority with the first grant made in 1967 to the National Folk Festival Association. Folklife festivals are now celebrated around the world to encourage and support the education and community engagement of diverse ethnic communities. Mingei (Japanese folk art movement). Mak Yong (Northern Malay Peninsular folk art dance).

Mexican handcrafts and folk art. Joget (Wider Malay folk art dance). Folk arts of Karnataka (India).

Folk Art and Ethnological Museum of Macedonia and Thrace. Folk Art Museum of Patras, Greece. Folk Art Society of America. IOV International Organization of Folk Art, in partnership with UNESCO. National Endowment for the Arts.

CIOFF: International Council of Organizations of Folklore Festivals and Folk Arts. Pennsylvania Folklore: Woven Together TV Program on textile arts. Folk Art Center and Guild, Asheville NC. Museum of International Folk Art. Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Museum.

The item "AMAZING IMPORTANT Letter & Folk Art Archive 1904 Civil War Confederate Veteran" is in sale since Tuesday, January 26, 2021. This item is in the category "Collectibles\Militaria\Civil War (1861-65)\Civil War Veterans' Items". The seller is "dalebooks" and is located in Rochester, New York. This item can be shipped worldwide.

- Modified Item: No

- Country/Region of Manufacture: United States

- Theme: Militaria