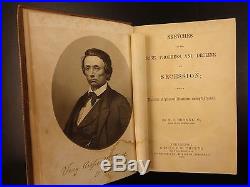

1862 1ed Sketches Decline of Secession Confederate CIVIL WAR Slavery Brownlow

Sketches Decline of Secession Confederate CIVIL WAR Slavery Brownlow. An important work on the Civil War, Confederate Secession, and slavery by William Brownlow. William Gannaway "Parson" Brownlow (August 29, 1805 April 29, 1877) was an American newspaper editor, minister, and politician. He served as Governor of Tennessee from 1865 to 1869 and as a United States Senator from Tennessee from 1869 to 1875.

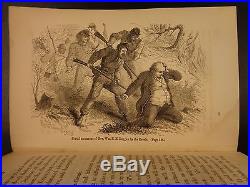

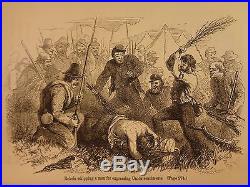

He rose to prominence in the 1840s as editor of the Whig, a polemical newspaper that promoted Whig Party ideals and opposed secession in the years leading up to the Civil War. Sketches of the rise, progress, and decline of secession : with a narrative of personal adventures among the rebels.Childs ; Cincinnati : Applegate & Co. 13 engravings including portrait frontispiece.

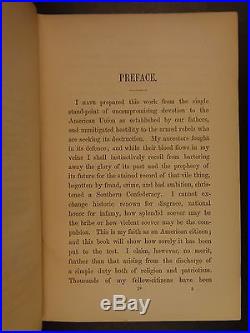

Wear as seen in photos. Complete with all 458 pages; plus indexes, prefaces, and such. 7.5in X 5in (19cm x 13cm).Brownlow's uncompromising and radical viewpoints made him one of the most divisive figures in Tennessee political history and one of the most controversial politicians of the Reconstruction-era South. Beginning his career as a Methodist circuit rider in the 1820s, Brownlow was both censured and praised by his superiors for his vicious verbal debates with rival missionaries of other persuasions. As a newspaper editor, he was notorious for his relentless personal attacks against his religious and political opponents, sometimes to the point of being physically assaulted. At the same time he was building a large base of fiercely loyal subscribers. [1] As a result of his persistent opposition to secession after the outbreak of the Civil War, he was jailed in December 1861, and was subsequently forced into exile in the North.

He joined the Radical Republicans and spent much of his term opposing the policies of his longtime political foe Andrew Johnson. [1] His gubernatorial policies, which were both autocratic and progressive, helped Tennessee become the first former Confederate state to be readmitted to the Union in 1866. [1] Brownlow's policy of disenfranchising ex-Confederates and enfranchising former slaves fueled the rise of the Ku Klux Klan in the late 1860s.

What made the Parson stand out was, more than anything else, his vitriolic tongue and pen. Over the course of his long career he took up many causes. These included not only Methodism, Whiggery, and the Union, but also temperance, Know-Nothingism, and slavery. His favorite method of promoting those causes was to chastise and ridicule his opponents, and few men could do so with as much venomous wit as he. Baptists, Presbyterians, Catholics, Mormons, Democrats, Republicans, secessionists, drunks, immigrants, and abolitionists-all were at one time or another on the receiving end of Brownlow's merciless broadsides.

Not surprisingly, he made many enemies. A number of them replied in kind; some tried to kill him. 10.3 Speeches and debates. Brownlow was born in Wythe County, Virginia, in 1805, the eldest son of Joseph Brownlow and Catherine Gannaway. Joseph Brownlow, an itinerant farmer, died in 1816, and Catherine Gannaway followed three months later, leaving William orphaned at the age of 10.

Brownlow and his four siblings were split up among relatives, with Brownlow spending the remainder of his childhood on his uncle John Gannaway's farm. At age 18, Brownlow went to Abingdon where he learned the trade of carpentry from another uncle, George Winniford. Engraving from Brownlow's book The Great Iron Wheel Examined, showing a Baptist minister changing clothes in front of horrified women after an Immersion. Attacks like this were typical of Brownlow's work. In 1825, Brownlow attended a camp meeting near Sulphur Springs, Virginia, where he experienced a dramatic spiritual rebirth.

He later recalled that, suddenly, all my anxieties were at an end, all my hopes were realized, my happiness was complete. [3]:4 He immediately abandoned the carpentry trade and began studying to become a Methodist minister. In Fall 1826, he attended the annual meeting of the Holston Conference of the Methodist Church in Abingdon. He applied to join the travelling ministry (commonly called "circuit riders"), and was admitted that year by Bishop Joshua Soule.In 1826, Soule gave Brownlow his first assignment the Black Mountain circuit in North Carolina. It was here that Brownlow first ran afoul of the Baptists who were spreading quickly throughout the Southern Appalachian region and developed an immediate dislike of them, considering them narrow-minded bigots who engaged in "dirty" rituals such as foot washing.

[3]:18 The following year, Brownlow was assigned to the circuit in Maryville, Tennessee, where there was a strong Presbyterian presence, and later recalled being constantly harassed by a young Presbyterian missionary who taunted him with Calvinistic criticisms of Methodism. The competition in Southern Appalachia for converts and their tithes among the Baptists, Methodists, and Presbyterians was fierce, and diatribes against rival religions were commonplace among missionaries. Brownlow, however, took such debates to a whole new level, attacking not only Baptist and Presbyterian theology, but also the character of his rival missionaries. In 1828, he was sued for slander, but the suit was dismissed. [3]:22 In 1832, Brownlow was assigned to the Pickens District in South Carolina, which he claimed was "overrun with Baptists" and nullifiers.

Unable to make headway in the district, he circulated a venomous 70-page pamphlet blasting the district's Baptists, and galloped safely back into the mountains as the district's enraged residents demanded he be hanged. [3]:25 Brownlow's run-in with the nullifiers would later influence his views on secession. In 1836, Brownlow married Eliza O'Brien, and the two settled down in her hometown of Elizabethton, Tennessee, where he took a job as a clerk at her family's iron foundry.

[4] Although Brownlow left the circuit shortly thereafter, he continued his staunch defense of Methodism in later newspaper columns and books, and for the remainder of his life he was known to friend and foe alike as Parson Brownlow. Main article: Brownlow's Whig. Ad in an 1848 issue of the Jonesborough Whig, attacking presidential candidate Lewis Cass. In the mid-1830s, Brownlow wrote several anti-nullification articles for Judge Thomas Emmerson's Jonesborough, Tennessee-based paper, the Washington Republican and Farmer's Journal.Impressed, Emmerson encouraged Brownlow to pursue a career in journalism. After Brownlow settled in nearby Elizabethton in 1839, rising local attorney T.

Nelson suggested he launch a newspaper to support Whig Party candidates in the upcoming elections. Brownlow partnered with publisher and former Emmerson associate Mason R. Lyon, and the two launched the Tennessee Whig in May 1839. Brownlow's vituperative editorial style quickly brought bitter division to Elizabethton, and he began quarreling with local Whig-turned-Democrat Landon Carter Haynes. After the Whig relocated to Jonesborough in May 1840, Brownlow accosted Haynes in the street and began beating him with a sword cane, prompting Haynes to draw a pistol and shoot him in the thigh.

[3]:39 Haynes was hired as editor of the Democratic Tennessee Sentinel the following year, and the two blasted each other in their respective papers for the next several years. In 1845, Brownlow ran against Andrew Johnson for the state's 1st District seat in the U. Using the Whig to support his campaign, he accused Johnson of being illegitimate, suggested Johnson's relatives were murderers and thieves, and stated that Johnson was an atheist. [3]:121 Johnson won the election by 1,300 votes, out of just over 10,000 votes cast. Brownlow, as he appeared on the frontispiece of his 1856 book, The Great Iron Wheel Examined.

Brownlow supported Whig policies such as a national bank, federal funding for internal improvements (more specifically, public improvements to the Moccasin Bend area of the Tennessee River near Chattanooga allowing for better steamboat transportation of goods to New Orleans), developing industries within northeast Tennessee, and a weakened presidency. [3]:111 He called Andrew Jackson the "greatest curse that ever yet befell this nation, "[6] and attacked Jackson's supporters, the Locofocos, in his 1844 book, A Political Register. [3]:113 While Brownlow steadfastly supported Whig candidates such as John Bell and James C. Jones, his true political idol was Kentucky senator Henry Clay. Clay was consistently Brownlow's first choice for the party's presidential candidate throughout the 1840s. [3]:112 Brownlow's son, John, recalled that one of the few times he ever saw his father cry was after he had received the news of Clay's defeat in the 1844 presidential election. In May 1849, Brownlow relocated the Whig to Knoxville, Tennessee, where he was already well known for his clashes with the Democratic Standard, which he had dubbed a filthy lying sheet. [6] Prior to his departure, an unknown assailant clubbed Brownlow in the head, leaving him bedridden for two weeks. He blamed this act on Knoxville's newspaper interests, who feared his competition. [3]:3744 Upon his arrival, he became embroiled in an editorial war with Knoxville Register editor John Miller McKee that lasted until McKee's departure in 1855. Brownlow joined the Sons of Temperance in 1850, [8] and promoted temperance policies in the Whig (one of his more common personal attacks was to accuse his opponents of being "drunkards"). Following the collapse of the Whig Party in the mid-1850s, he aligned himself with the Know Nothing movement, as he had long shared this movement's anti-Catholic and nativist sentiments. [3]:125 In 1856, he published a book, Americanism Contrasted with Foreignism, Romanism and Bogus Democracy, which attacked Catholicism, foreigners and Democratic politicians. In the late 1850s, Brownlow turned his attention to Knoxville's Democratic Party leaders and their associates. He quarreled with the radical Southern Citizen, a pro-secession newspaper published by businessman William G.Swan and Irish Patriot John Mitchel (who spent time in Knoxville while in exile), and on at least one occasion, threatened Swan with a revolver. [3]:49 Following the failure of the Bank of East Tennessee in 1858, Brownlow ruthlessly assailed its directors. Crozier and William Churchwell to flee the state, and drove John H.

He sued another director, J. Ramsey, winning a civil judgement on behalf of the bank's depositers. The item "1862 1ed Sketches Decline of Secession Confederate CIVIL WAR Slavery Brownlow" is in sale since Wednesday, December 13, 2017. This item is in the category "Books\Antiquarian & Collectible". The seller is "schilb_antique_books" and is located in Columbia, Missouri. This item can be shipped worldwide.- Subject: Americana

- Binding: Hardcover

- Special Attributes: 1st Edition

- Year Printed: 1862

- Language: English

- Original/Facsimile: Original