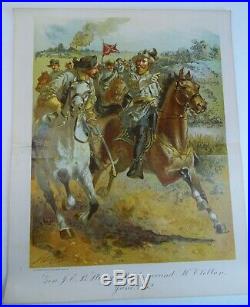

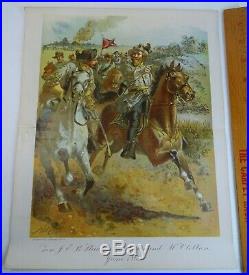

RARE Antique Litho Print JEB Stuart's Raid Confederate 1862 Civil War 1900

Antique - Old Original Print. Stuart's Raid around McClellan. For offer - a very nice old print! Fresh from an estate in Upstate NY. Never offered on the market until now.

Vintage, Old, antique, Original - NOT a Reproduction - Guaranteed!! Rint shows Stuart on horseback. Printer information at lower lh corner: 1900, by Jones Bros. Signed by artist at lower right - H. Easures 12 1/4 x 10 inches.

Originally issued in book form, folded in half - thus the fold mark across center. NOTE: will be sent folded in half, as found and as issued. In good to very good condition. Also has another crease below the fold mark, slight separation at left edge, with small crease, and faint crease to lower lh edge. If you collect American art history, Americana, Civil War, military, Jones Brothers, art printing, etc.

This is a nice one for your paper or ephemera collection. James Ewell Brown "Jeb" Stuart (February 6, 1833 May 12, 1864) was a United States Army officer from Virginia who became a Confederate States Army general during the American Civil War.

He was known to his friends as "Jeb", from the initials of his given names. Stuart was a cavalry commander known for his mastery of reconnaissance and the use of cavalry in support of offensive operations. While he cultivated a cavalier image (red-lined gray cape, yellow sash, hat cocked to the side with an ostrich plume, red flower in his lapel, often sporting cologne), his serious work made him the trusted eyes and ears of Robert E. Lee's army and inspired Southern morale.Stuart graduated from West Point in 1854, and served in Texas and Kansas with the U. He was a veteran of the frontier conflicts with Native Americans and the violence of Bleeding Kansas, and he participated in the capture of John Brown at Harpers Ferry. He resigned, when his home state of Virginia seceded, to serve in the Confederate Army, first under Stonewall Jackson in the Shenandoah Valley, but then in increasingly important cavalry commands of the Army of Northern Virginia, playing a role in all of that army's campaigns until his death. He established a reputation as an audacious cavalry commander and on two occasions (during the Peninsula Campaign and the Maryland Campaign) circumnavigated the Union Army of the Potomac, bringing fame to himself and embarrassment to the North. At the Battle of Chancellorsville, he distinguished himself as a temporary commander of the wounded Stonewall Jackson's infantry corps.

Stuart's most famous campaign, the Gettysburg Campaign, was flawed when his long separation from Lee's army, left Lee unaware of Union troop movements so that Lee was surprised and almost trapped at the Battle of Gettysburg. Stuart received significant criticism from the Southern press as well as the postbellum proponents of the Lost Cause movement. During the 1864 Overland Campaign, Union Maj.Philip Sheridan's cavalry launched an offensive to defeat Stuart, who was mortally wounded at the Battle of Yellow Tavern. Stuart's widow wore black for the rest of her life in remembrance of her deceased husband. Laurel Hill Farm overview, 2017. Stuart was born at Laurel Hill Farm, a plantation in Patrick County, Virginia, near the border with North Carolina.

He was of Scottish American and Scots-Irish background. [4] He was the eighth of eleven children and the youngest of the five sons to survive past early age. [5] His great-grandfather, Major Alexander Stuart, commanded a regiment at the Battle of Guilford Court House during the American Revolutionary War.

[6] His father, Archibald Stuart, was a War of 1812 veteran, slaveholder, attorney, and Democratic politician who represented Patrick County in both houses of the Virginia General Assembly, and also served one term in the United States House of Representatives. [7] Archibald was a cousin of Alexander Hugh Holmes Stuart.

Elizabeth Letcher Pannill Stuart, Jeb's mother, who was known as a strict religious woman with a good sense for business, ran the family farm. Stuart was educated at home by his mother and tutors until the age of twelve, when he left Laurel Hill to be educated by various teachers in Wytheville, Virginia, and at the home of his aunt Anne (Archibald's sister) and her husband Judge James Ewell Brown (Stuart's namesake) at Danville. [8] He entered Emory and Henry College when he was fifteen, and attended from 1848 to 1850.

During the summer of 1848, Stuart attempted to enlist in the U. Army, but was rejected as underaged. He obtained an appointment in 1850 to the United States Military Academy at West Point, New York, from Representative Thomas Hamlet Averett, the man who had defeated his father in the 1848 election. [10] Stuart was a popular student and was happy at the Academy. Although not handsome in his teen years, his classmates called him by the nickname "Beauty", which they described as his personal comeliness in inverse ratio to the term employed.

"[11] He possessed a chin "so short and retiring as positively to disfigure his otherwise fine countenance. " He quickly grew a beard after graduation and a fellow officer remarked that he was "the only man he ever saw that [a] beard improved. Lee was appointed superintendent of the academy in 1852, and Stuart became a friend of the Lee family, seeing them socially on frequent occasions. Lee's nephew, Fitzhugh Lee, also arrived at the academy in 1852.

In Stuart's final year, in addition to achieving the cadet rank of second captain of the corps, he was one of eight cadets designated as honorary "cavalry officers" for his skills in horsemanship. [13] Stuart graduated 13th in his class of 46 in 1854. He ranked tenth in his class in cavalry tactics.

Although he enjoyed the civil engineering curriculum at the academy and did well in mathematics, his poor drawing skills hampered his engineering studies, and he finished 29th in that discipline. A Stuart family tradition says he deliberately degraded his academic performance in his final year to avoid service in the elite, but dull, Corps of Engineers.

Stuart was commissioned a brevet second lieutenant and assigned to the U. Regiment of Mounted Riflemen in Texas. [1] After an arduous journey, he reached Fort Davis on January 28, 1855, and was a leader for three months on scouting missions over the San Antonio to El Paso Road.[15] He was soon transferred to the newly formed 1st Cavalry Regiment (1855) at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas Territory, where he became regimental quartermaster[16] and commissary officer under the command of Col. [17] He was promoted to first lieutenant in 1855. Also in 1855, Stuart met Flora Cooke, the daughter of the commander of the 2nd U.

Dragoon Regiment, Lieutenant Colonel Philip St. Burke Davis described Flora as "an accomplished horsewoman, and though not pretty, an effective charmer, " to whom Stuart succumbed with hardly a struggle. [18] They became engaged in September, less than two months after meeting.

Stuart humorously wrote of his rapid courtship in Latin, "Veni, Vidi, Victus sum" (I came, I saw, I was conquered). Although a gala wedding was planned for Fort Riley, Kansas, the death of Stuart's father on September 20 caused a change of plans and the marriage on November 14 was small and limited to family witnesses. Stuart's leadership capabilities were soon recognized. He was a veteran of the frontier conflicts with Native Americans and the antebellum violence of Bleeding Kansas. He was wounded on July 29, 1857, while fighting at Solomon River, Kansas, against the Cheyenne.

Sumner ordered a charge with drawn sabers against a wave of Indian arrows. Scattering the warriors, Stuart and three other lieutenants chased one down, whom Stuart wounded in the thigh with his pistol. The Cheyenne turned and fired at Stuart with an old-fashioned pistol, striking him in the chest with a bullet, which did little more damage than to pierce the skin.

Their first child, a girl, had been born in 1856 but died the same day. On November 14, 1857, Flora gave birth to another daughter, whom the parents named Flora after her mother. The family relocated in early 1858 to Fort Riley, where they remained for three years. In 1859, Stuart developed a new piece of cavalry equipment, for which he received patent number 25,684 on October 4a saber hook, or an improved method of attaching sabers to belts.

Of Philadelphia to manufacture his hook. To discuss government contracts, and in conjunction with his application for an appointment into the quartermaster department, Stuart heard about John Brown's raid on the U. Stuart volunteered to be aide-de-camp to Col. Lee and accompanied Lee with a company of U. Marines from the Marine Barracks, 8th & I, Washington, DC. [23] and four companies of Maryland militia. While delivering Lee's written surrender ultimatum to the leader of the group, who had been calling himself Isaac Smith, Stuart recognized "Old Osawatomie Brown" from his days in Kansas. Stuart was promoted to captain on April 22, 1861, but resigned from the U. Army on May 3, 1861, to join the Confederate States Army, following the secession of Virginia. His letter of resignation, sent from Cairo, Illinois, was accepted by the War Department on May 14.[25] Upon learning that his father-in-law, Col. Cooke, would remain in the U. Army during the coming war, Stuart wrote to his brother-in-law future Confederate Brig.

John Rogers Cooke, He will regret it but once, and that will be continuously. [26] On June 26, 1860, Flora gave birth to a son, Philip St.George Cooke Stuart, but his father changed the name to James Ewell Brown Stuart, Jr. ("Jimmie"), in late 1861 out of disgust with his father-in-law.

Stuart was commissioned as a lieutenant colonel of Virginia Infantry in the Confederate Army on May 10, 1861. Lee, now commanding the armed forces of Virginia, ordered him to report to Colonel Thomas J.

Jackson at Harper's Ferry. Jackson chose to ignore Stuart's infantry designation and assigned him on July 4 to command all the cavalry companies of the Army of the Shenandoah, organized as the 1st Virginia Cavalry Regiment. [28] He was promoted to colonel on July 16. [Stuart] is a rare man, wonderfully endowed by nature with the qualities necessary for an officer of light cavalry. Calm, firm, acute, active, and enterprising, I know no one more competent than he to estimate the occurrences before him at their true value.If you add to this army a real brigade of cavalry, you can find no better brigadier-general to command it. Johnston, letter to Confederate President Jefferson Davis, August 1861[29]. After early service in the Shenandoah Valley, Stuart led his regiment in the First Battle of Bull Run, and participated in the pursuit of the retreating Federals. He then commanded the Army's outposts along the upper Potomac River until given command of the cavalry brigade for the army then known as the Army of the Potomac (later named the Army of Northern Virginia). He was promoted to brigadier general on September 24, 1861.

In 1862, the Union Army of the Potomac began its Peninsula Campaign against Richmond, Virginia, and Stuart's cavalry brigade assisted Gen. Johnston's army as it withdrew up the Virginia Peninsula in the face of superior numbers.

Stuart fought at the Battle of Williamsburg, but in general the terrain and weather on the Peninsula did not lend themselves to cavalry operations. Lee became commander of the Army of Northern Virginia, he requested that Stuart perform reconnaissance to determine whether the right flank of the Union army was vulnerable.Stuart set out with 1,200 troopers on the morning of June 12 and, having determined that the flank was indeed vulnerable, took his men on a complete circumnavigation of the Union army, returning after 150 miles on July 15 with 165 captured Union soldiers, 260 horses and mules, and various quartermaster and ordnance supplies. His men met no serious opposition from the more decentralized Union cavalry, coincidentally commanded by his father-in-law, Col. The maneuver was a public relations sensation and Stuart was greeted with flower petals thrown in his path at Richmond. He had become as famous as Stonewall Jackson in the eyes of the Confederacy.

Early in the Northern Virginia Campaign, Stuart was promoted to major general on July 25, 1862, and his command was upgraded to the Cavalry Division. [31] He was nearly captured and lost his signature plumed hat and cloak to pursuing Federals during a raid in August, but in a retaliatory raid at Catlett's Station the following day, managed to overrun Union army commander Maj. John Pope's headquarters, and not only captured Pope's full uniform, but also intercepted orders that provided Lee with valuable intelligence concerning reinforcements for Pope's army. At the Second Battle of Bull Run (Second Manassas), Stuart's cavalry followed the massive assault by Longstreet's infantry against Pope's army, protecting its flank with artillery batteries. Beverly Robertson's brigade to pursue the Federals and in a sharp fight against Brig.John Buford's brigade, Col. Munford's 2nd Virginia Cavalry was overwhelmed until Stuart sent in two more regiments as reinforcements.

Buford's men, many of whom were new to combat, retreated across Lewis's Ford and Stuart's troopers captured over 300 of them. Stuart's men harassed the retreating Union columns until the campaign ended at the Battle of Chantilly.

During the Maryland Campaign of September 1862, Stuart's cavalry screened the army's movement north. He bears some responsibility for Robert E.

Lee's lack of knowledge of the position and celerity of the pursuing Army of the Potomac under George B. For a five-day period, Stuart rested his men and entertained local civilians at a gala ball at Urbana, Maryland. His reports make no reference to intelligence gathering by his scouts or patrols. [33] As the Union Army drew near to Lee's divided army, Stuart's men skirmished at various points on the approach to Frederick and Stuart was not able to keep his brigades concentrated enough to resist the oncoming tide.

He misjudged the Union routes of advance, ignorant of the Union force threatening Turner's Gap, and required assistance from the infantry of Maj. Hill to defend the South Mountain passes in the Battle of South Mountain. [34] His horse artillery bombarded the flank of the Union army as it opened its attack in the Battle of Antietam. By mid-afternoon, Stonewall Jackson ordered Stuart to command a turning movement with his cavalry against the Union right flank and rear, which if successful would be followed up by an infantry attack from the West Woods.Stuart began probing the Union lines with more artillery barrages, which were answered with "murderous" counterbattery fire and the cavalry movement intended by Jackson was never launched. Stuart and Jackson were an unlikely pair: one outgoing, the other introverted; one flashily uniformed, the other plainly dressed; one Prince Rupert and the other Cromwell. Yet Stuart's self-confidence, penchant for action, deep love of Virginia, and total abstinence from such vices as alcohol, tobacco, and pessimism endeared him to Jackson.

Stuart was the only man in the Confederacy [who] could make Jackson laughand who dared to do so. Three weeks after Lee's army had withdrawn back to Virginia, on October 1012, 1862, Stuart performed another of his audacious circumnavigations of the Army of the Potomac, his Chambersburg Raid126 miles in under 60 hours, from Darkesville, West Virginia to as far north as Mercersburg, Pennsylvania and Chambersburg and around to the east through Emmitsburg, Maryland and south through Hyattstown, Maryland and White's Ford to Leesburg, Virginiaonce again embarrassing his Union opponents and seizing horses and supplies, but at the expense of exhausted men and animals, without gaining much military advantage. Jubal Early referred to it as "the greatest horse stealing expedition" that only "annoyed" the enemy. [37] Stuart gave his friend Jackson a fine, new officer's tunic, trimmed with gold lace, commissioned from a Richmond tailor, which he thought would give Jackson more of the appearance of a proper general (something to which Jackson was notoriously indifferent).

McClellan pushed his army slowly south, urged by President Lincoln to pursue Lee, crossing the Potomac starting on October 26. As Lee began moving to counter this, Stuart screened Longstreet's Corps and skirmished numerous times in early November against Union cavalry and infantry around Mountville, Aldie, and Upperville.

On November 6, Stuart received sad news by telegram that his daughter Flora had died just before her fifth birthday of typhoid fever on November 3. In the December 1862 Battle of Fredericksburg, Stuart and his cavalrymost notably his horse artillery under Major John Pelhamprotected Stonewall Jackson's flank at Hamilton's Crossing. General Lee commended his cavalry, which effectually guarded our right, annoying the enemy and embarrassing his movements by hanging on his flank, and attacking when the opportunity occurred. Stuart reported to Flora the next day that he had been shot through his fur collar but was unhurt.

After Christmas, Lee ordered Stuart to conduct a raid north of the Rappahannock River to penetrate the enemy's rear, ascertain if possible his position & movements, & inflict upon him such damage as circumstances will permit. With 1,800 troopers and a horse artillery battery assigned to the operation, Stuart's raid reached as far north as four miles south of Fairfax Court House, seizing 250 prisoners, horses, mules, and supplies.Tapping telegraph lines, his signalmen intercepted messages between Union commanders and Stuart sent a personal telegram to Union Quartermaster General Montgomery C. Meigs, General Meigs will in the future please furnish better mules; those you have furnished recently are very inferior. On March 17, 1863, Stuart's cavalry clashed with a Union raiding party at Kelly's Ford.

The minor victory was marred by the death of Major Pelham, which caused Stuart profound grief, as he thought of him as close as a younger brother. He wrote to a Confederate Congressman, The noble, the chivalric, the gallant Pelham is no more. Let the tears of agony we have shed, and the gloom of mourning throughout my command bear witness. Flora was pregnant at the time and Stuart told her that if it were a boy, he wanted him to be named John Pelham Stuart. Virginia Pelham Stuart was born October 9.

A map showing Stuart's attack on General Daniel Sickles's position in the western outskirts of Chancellorsville. At the Battle of Chancellorsville, Stuart accompanied Stonewall Jackson on his famous flanking march of May 2, 1863, and started to pursue the retreating soldiers of the Union XI Corps when he received word that both Jackson and his senior division commander, Maj. Hill, bypassing the next most senior infantry general in the corps, Brig. Rodes, sent a message ordering Stuart to take command of the Second Corps. Although the delays associated with this change of command effectively ended the flanking attack the night of May 2, Stuart performed credibly as an infantry corps commander the following day, launching a strong and well-coordinated attack against the Union right flank at Chancellorsville. When Union troops abandoned Hazel Grove, Stuart had the presence of mind to quickly occupy it and bombard the Union positions with artillery. It is hard to see how Jeb Stuart, in a new command, a cavalryman commanding infantry and artillery for the first time, could have done a better job. The astute Porter Alexander believed all credit was due: Altogether, I do not think there was a more brilliant thing done in the war than Stuart's extricating that command from the extremely critical position in which he found it. Stonewall Jackson died on May 10 and Stuart was once again devastated by the loss of a close friend, telling his staff that the death was a national calamity. " Jackson's wife, Mary Anna, wrote to Stuart on August 1, thanking him for a note of sympathy: "I need not assure you of which you already know, that your friendship & admiration were cordially reciprocated by him. I have frequently heard him speak of Gen'l Stuart as one of his warm personal friends, & also express admiration for your Soldierly qualities. The grand review of June 5 was surely the proudest day of Jeb Stuart's thirty years.As he led a cavalcade of resplendent staff officers to the reviewing stand, trumpeters heralded his coming and women and girls strewed his path with flowers. Before all of the spectators the assembled cavalry brigade stretched a mile and a half. After Stuart and his entourage galloped past the line in review, the troopers in their turn saluted the reviewing stand in columns of squadrons. In performing a second "march past, " the squadrons started off at a trot, then spurred to a gallop. Drawing sabers and breaking into the Rebel yell, the troopers rush toward the horse artillery drawn up in battery.

The gunners responded defiantly, firing blank charges. Amidst this tumult of cannon fire and thundering hooves, a number of ladies swooned in their escorts' arms. A map showing Union actions and Stuart's responses at the Battle of Brandy Station. Battle of Brandy Station, June 9, 1863. Returning to the cavalry for the Gettysburg Campaign, Stuart endured the two low points in his career, starting with the Battle of Brandy Station, the largest predominantly cavalry engagement of the war.

By June 5, two of Lee's infantry corps were camped in and around Culpeper. Six miles northeast, holding the line of the Rappahannock River, Stuart bivouacked his cavalry troopers, mostly near Brandy Station, screening the Confederate Army against surprise by the enemy. Stuart requested a full field review of his troops by Gen.

This grand review on June 5 included nearly 9,000 mounted troopers and four batteries of horse artillery, charging in simulated battle at Inlet Station, about two miles (three km) southwest of Brandy Station. Lee was not able to attend the review, however, so it was repeated in his presence on June 8, although the repeated performance was limited to a simple parade without battle simulations. [48] Despite the lower level of activity, some of the cavalrymen and the newspaper reporters at the scene complained that all Stuart was doing was feeding his ego and exhausting the horses.Lee ordered Stuart to cross the Rappahannock the next day and raid Union forward positions, screening the Confederate Army from observation or interference as it moved north. Anticipating this imminent offensive action, Stuart ordered his tired troopers back into bivouac around Brandy Station. Army of the Potomac commander Maj. Joseph Hooker interpreted Stuart's presence around Culpeper to be indicative of preparations for a raid on his army's supply lines.

In reaction, he ordered his cavalry commander, Maj. Alfred Pleasonton, to take a combined arms force of 8,000 cavalrymen and 3,000 infantry on a "spoiling raid" to "disperse and destroy" the 9,500 Confederates. [50] Pleasonton's force crossed the Rappahannock in two columns on June 9, 1863, the first crossing at Beverly's Ford Brig.

John Buford's division catching Stuart by surprise, waking him and his staff to the sound of gunfire. The second crossing, at Kelly's Ford, surprised Stuart again, and the Confederates found themselves assaulted from front and rear in a spirited melee of mounted combat.A series of confusing charges and countercharges swept back and forth across Fleetwood Hill, which had been Stuart's headquarters the previous night. After ten hours of fighting, Pleasonton ordered his men to withdraw across the Rappahannock. Stuart is to be the eyes and ears of the army we advise him to see more, and be seen less. Stuart has suffered no little in public estimation by the late enterprises of the enemy. Richmond Enquirer, June 12, 1863[52].

Although Stuart claimed a victory because the Confederates held the field, Brandy Station is considered a tactical draw, and both sides came up short. Pleasonton was not able to disable Stuart's force at the start of an important campaign and he withdrew before finding the location of Lee's infantry nearby. However, the fact that the Southern cavalry had not detected the movement of two large columns of Union cavalry, and that they fell victim to a surprise attack, was an embarrassment that prompted serious criticism from fellow generals and the Southern press. The fight also revealed the increased competency of the Union cavalry, and foreshadowed the decline of the formerly invincible Southern mounted arm.

Stuart's ride in the Gettysburg Campaign. A map showing Union and Confederate movements at the corps level during the opening phases of the Gettysburg Campaign, with Stuart's cavalry ride shown with a red dotted line. Stuart's ride (shown with a red dotted line) during the Gettysburg Campaign, June 3 July 3, 1863. Following a series of small cavalry battles in June as Lee's army began marching north through the Shenandoah Valley, Stuart may have had in mind the glory of circumnavigating the enemy army once again, desiring to erase the stain on his reputation of the surprise at Brandy Station. General Lee gave orders to Stuart on June 22 on how he was to participate in the march north, and the exact nature of those orders has been argued by the participants and historians ever since, but the essence was that he was instructed to guard the mountain passes with part of his force while the Army of Northern Virginia was still south of the Potomac and that he was to cross the river with the remainder of the army and screen the right flank of Ewell's Second Corps.

Instead of taking a direct route north near the Blue Ridge Mountains, however, Stuart chose to reach Ewell's flank by taking his three best brigades those of Brig. Chambliss, the latter replacing the wounded Brig. "Rooney" Lee between the Union army and Washington, moving north through Rockville to Westminster and on into Pennsylvania, hoping to capture supplies along the way and cause havoc near the enemy capital. Stuart and his three brigades departed Salem Depot at 1 a.

Unfortunately for Stuart's plan, the Union army's movement was underway and his proposed route was blocked by columns of Federal infantry, forcing him to veer farther to the east than either he or General Lee had anticipated. This prevented Stuart from linking up with Ewell as ordered and deprived Lee of the use of his prime cavalry force, the "eyes and ears" of the army, while advancing into unfamiliar enemy territory. Stuart's command crossed the Potomac River at 3 a. At Rockville they captured a wagon train of 140 brand-new, fully loaded wagons and mule teams. This wagon train would prove to be a logistical hindrance to Stuart's advance, but he interpreted Lee's orders as placing importance on gathering supplies. The proximity of the Confederate raiders provoked some consternation in the national capital and two Union cavalry brigades and an artillery battery were sent to pursue the Confederates. Stuart supposedly said that were it not for his fatigued horses he would have marched down the 7th Street Road [and] took Abe & Cabinet prisoners.In Westminster on June 29, his men clashed briefly with and overwhelmed two companies of Union cavalry, chasing them a long distance on the Baltimore road, which Stuart claimed caused a "great panic" in the city of Baltimore. [57] The head of Stuart's column encountered Brig.

Judson Kilpatrick's cavalry as it passed through Hanover and scattered it on June 30; the Battle of Hanover ended after Kilpatrick's men regrouped and drove the Confederates out of town. Stuart's brigades had been better positioned to guard their captured wagon train than to take advantage of the encounter with Kilpatrick. After a 20-mile trek in the dark, his exhausted men reached Dover on the morning of July 1, as the Battle of Gettysburg was commencing without them. Stuart headed next for Carlisle, hoping to find Ewell.

He lobbed a few shells into town during the early evening of July 1 and burned the Carlisle Barracks before withdrawing to the south towards Gettysburg. He and the bulk of his command reached Lee at Gettysburg the afternoon of July 2. He ordered Wade Hampton to cover the left rear of the Confederate battle lines, and Hampton fought with Brig. George Armstrong Custer at the Battle of Hunterstown before joining Stuart at Gettysburg. When Stuart arrived at Gettysburg on the afternoon of July 2bringing with him the caravan of captured Union supply wagonshe received a rare rebuke from Lee.

No one witnessed the private meeting between Lee and Stuart, but reports circulated at headquarters that Lee's greeting was abrupt and frosty. " Colonel Edward Porter Alexander wrote, "Although Lee said only,'Well, General, you are here at last,' his manner implied rebuke, and it was so understood by Stuart. [60] On the final day of the battle, Stuart was ordered to get into the enemy's rear and disrupt its line of communications at the same time Pickett's Charge was sent against the Union positions on Cemetery Ridge, but his attack on East Cavalry Field was repulsed by Union cavalry under Brig.

David Gregg and George Custer. During the retreat from Gettysburg, Stuart devoted his full attention to supporting the army's movement, successfully screening against aggressive Union cavalry pursuit and escorting thousands of wagons with wounded men and captured supplies over difficult roads and through inclement weather.Numerous skirmishes and minor battles occurred during the screening and delaying actions of the retreat. Stuart's men were the final units to cross the Potomac River, returning to Virginia in wretched conditioncompletely worn out and broken down. The failure to crush the Federal army in Pennsylvania in 1863, in the opinion of almost all of the officers of the Army of Northern Virginia, can be expressed in five wordsthe absence of the cavalry. The Gettysburg Campaign was the most controversial of Stuart's career. He became one of the scapegoats (along with James Longstreet) blamed for Lee's loss at Gettysburg by proponents of the postbellum Lost Cause movement, such as Jubal Early.

[64] This was fueled in part by opinions of less partisan writers, such as Stuart's subordinate, Thomas L. Rosser, who stated after the war that Stuart did, on this campaign, undoubtedly, make the fatal blunder which lost us the battle of Gettysburg. In General Lee's report on the campaign, he wrote. The absence of the cavalry rendered it impossible to obtain accurate information. By the route [Stuart] pursued, the Federal Army was interposed between his command and our main body, preventing any communication with him until his arrival at Carlisle. The march toward Gettysburg was conducted more slowly than it would have been had the movements of the Federal Army been known. One of the most forceful postbellum defenses of Stuart was by Col.Mosby, who had served under him during the campaign and was fiercely loyal to the late general, writing, He made me all that I was in the war. But for his friendship I would never have been heard of. He wrote numerous articles for popular publications and published a book length treatise in 1908, a work that relied on his skills as a lawyer to refute categorically all of the claims laid against Stuart.

Historians remain divided on how much the defeat at Gettysburg was due to Stuart failure to keep Lee informed. Longacre argues that Lee deliberately gave Stuart wide discretion in his orders. Coddington refers to the "tragedy" of Stuart in the Gettysburg Campaign and judges that when Fitzhugh Lee raised the question of "whether Stuart exercised the discretion undoubtedly given to him, judiciously, " the answer is no. Agreeing that Stuart's absence permitted Lee to be surprised at Gettysburg, Coddington points out that the Union commander, was just as surprised.

David Petruzzi have concluded that there was "plenty of blame to go around" and the fault should be divided between Stuart, the lack of specificity in Lee's orders, and Richard S. Ewell, who might have tried harder to link up with Stuart northeast of Gettysburg. Wert acknowledges that Lee, his officers, and fighting by the Army of the Potomac bear the responsibility for the Confederate loss at Gettysburg, but states that Stuart failed Lee and the army in the reckoning at Gettysburg. Lee trusted him and gave him discretion, but Stuart acted injudiciously. Although Stuart was not reprimanded or disciplined in any official way for his role in the Gettysburg campaign, it is noteworthy that his appointment to corps command on September 9, 1863, did not carry with it a promotion to lieutenant general. Edward Bonekemper wrote that since all other corps commanders in the Army of Northern Virginia carried this rank, Lee's decision to keep Stuart at major general rank, while at the same time promoting Stuart's subordinates Wade Hampton and Fitzhugh Lee to major generals, could be considered an implied rebuke. Wert wrote that there is no evidence Lee considered Stuart's performance during the Gettysburg Campaign and that it is more likely that Lee thought the responsibilities in command of a cavalry corps did not equal those of an infantry corps. Fall 1863 and the 1864 Overland Campaign.[The cavalry's success in the Bristoe Campaign can be attributed] to the generalship, boldness, and untiring energy of Major-General Stuart, for it was he who directed every movement of importance, and his generalship, boldness, and energy won the unbounded confidence of officers and men, and gave the prestige of success. Confederate Colonel Oliver Funsten[69]. A map of the Bristoe Campaign. A map of the 1864 Overland Campaign, including the location of the Battle of Yellow Tavern. The 1864 Overland Campaign, including the Battle of Yellow Tavern.

Lee reorganized his cavalry on September 9, creating a Cavalry Corps for Stuart with two divisions of three brigades each. In the Bristoe Campaign, Stuart was assigned to lead a broad turning movement in an attempt to get into the enemy's rear, but General Meade skillfully withdrew his army without leaving Stuart any opportunities to take advantage of. On October 13, Stuart blundered into the rear guard of the Union III Corps near Warrenton, resulting in the First Battle of Auburn.

Ewell's corps was sent to rescue him, but Stuart hid his troopers in a wooded ravine until the unsuspecting III Corps moved on, and the assistance was not necessary. As Meade withdrew towards Manassas Junction, brigades from the Union II Corps fought a rearguard action against Stuart's cavalry and the infantry of Brig. Harry Hays's division near Auburn on October 14.

Stuart's cavalry boldly bluffed Warren's infantry and escaped disaster. After the Confederate repulse at Bristoe Station and an aborted advance on Centreville, Stuart's cavalry shielded the withdrawal of Lee's army from the vicinity of Manassas Junction. Judson Kilpatrick's Union cavalry pursued Stuart's cavalry along the Warrenton Turnpike, but were lured into an ambush near Chestnut Hill and routed. The Federal troopers were scattered and chased five miles (eight km) in an affair that came to be known as the "Buckland Races". The Southern press began to mute its criticism of Stuart following his successful performance during the fall campaign.Grant's offensive against Lee in the spring of 1864, began at the Battle of the Wilderness, where Stuart aggressively pushed Thomas L. Rosser's Laurel Brigade into a fight against George Custer's better-armed Michigan Brigade, resulting in significant losses.

General Lee sent a message to Stuart: It is very important to save your Cavalry & not wear it out. You must use your good judgment to make any attack which may offer advantages. As the armies maneuvered toward their next confrontation at Spotsylvania Court House, Stuart's cavalry fought delaying actions against the Union cavalry.

His defense at Laurel Hill, also directing the infantry of Brig. Kershaw, skillfully delayed the advance of the Federal army for nearly 5 critical hours. Southern Troopers Song, Dedicated to Gen'l.

Stuart and his gallant Soldiers, Sheet music, Danville, Virginia, c. The commander of the Army of the Potomac, Maj. George Meade, and his cavalry commander, Maj.

Philip Sheridan, quarreled about the Union cavalry's performance in the first two engagements of the Overland Campaign. Sheridan heatedly asserted that he wanted to concentrate all of cavalry, move out in force against Stuart's command, and whip it. " Meade reported the comments to Grant, who replied "Did Sheridan say that? Well, he generally knows what he is talking about.

Let him start right out and do it. Sheridan immediately organized a raid against Confederate supply and railroad lines close to Richmond, which he knew would bring Stuart to battle. Sheridan moved aggressively to the southeast, crossing the North Anna River and seizing Beaver Dam Station on the Virginia Central Railroad, where his men captured a train, liberating 3,000 Union prisoners and destroying more than one million rations and medical supplies destined for Lee's army.

Stuart dispatched a force of about 3,000 cavalrymen to intercept Sheridan's cavalry, which was more than three times their numbers. As he rode in pursuit, accompanied by his aide, Maj.Venable, they were able to stop briefly along the way to be greeted by Stuart's wife, Flora, and his children, Jimmie and Virginia. Venable wrote of Stuart, He told me he never expected to live through the war, and that if we were conquered, that he did not want to live. The Battle of Yellow Tavern occurred May 11, at an abandoned inn located six miles (9.7 km) north of Richmond. The Confederate troopers tenaciously resisted from the low ridgeline bordering the road to Richmond, fighting for over three hours. After receiving a scouting report from Texas Jack Omohundro, Stuart led a countercharge and pushed the advancing Union troopers back from the hilltop as Stuart, on horseback, shouted encouragement while firing his revolver at the Union troopers.

As the 5th Michigan Cavalry streamed in retreat past Stuart, a dismounted Union private, 44-year-old John A. Huff, turned and shot Stuart with his. 44-caliber revolver from a distance of 1030 yards. Huff's bullet struck Stuart in the left side.It then sliced through his stomach and exited his back, one inch to the right of his spine. [75] Stuart suffered great pain as an ambulance took him to Richmond to await his wife's arrival at the home of Dr.

As he was being driven from the field in an ambulance wagon, Stuart noticed disorganized ranks of retreating men and called out to them his last words on the battlefield: Go back, go back, and do your duty, as I have done mine, and our country will be safe. I had rather die than be whipped. [76] Stuart ordered his sword and spurs be given to his son.As his aide Major McClellan left his side, Confederate President Jefferson Davis came in, took General Stuart's hand, and asked, General, how do you feel? " Stuart answered "Easy, but willing to die, if God and my country think I have fulfilled my destiny and done my duty.

He died at 7:38 p. On May 12, the following day, before Flora Stuart reached his side. He was 31 years old. Stuart was buried in Richmond's Hollywood Cemetery. Upon learning of Stuart's death, General Lee is reported to have said that he could hardly keep from weeping at the mere mention of Stuart's name and that Stuart had never given him a bad piece of information. Flora wore the black of mourning for the remainder of her life, and never remarried. She lived in Saltville, Virginia, for 15 years after the war, where she opened and taught at a school in a log cabin. She worked from 1880 to 1898 as principal of the Virginia Female Institute in Staunton, Virginia, a position for which Robert E. Lee had recommended her before his death ten years earlier. [78] In 1907, the Institute was renamed Stuart Hall School in her honor. Upon the death of her daughter Virginia, from complications in childbirth in 1898, Flora resigned from the Institute and moved to Norfolk, Virginia, where she helped Virginia's widower, Robert Page Waller, in raising her grandchildren. She died in Norfolk on May 10, 1923, after striking her head in a fall on a city sidewalk.She is buried alongside her husband and their daughter, Little Flora, in Hollywood Cemetery in Richmond. Stuart's grave in Hollywood Cemetery, Richmond, with temporary marker, 1865.

Gravesite of Jeb and Flora Stuart, Hollywood Cemetery. Like his intimate friend, Stonewall Jackson, General J. Stuart was a legendary figure and is considered one of the greatest cavalry commanders in American history. His friend from his federal army days, Union Maj.

John Sedgwick, said that Stuart was the greatest cavalry officer ever foaled in America. [80] Jackson and Stuart, both of whom were killed in battle, had colorful public images, although the latter seems to have been more deliberately crafted.

Stuart had been the Confederacy's knight-errant, the bold and dashing cavalier, attired in a resplendent uniform, plumed hat, and cape. Amid a slaughterhouse, he had embodied chivalry, clinging to the pageantry of a long-gone warrior. He crafted the image carefully, and the image befitted him. He saw himself as the Southern people envisaged him. They needed a knight; he needed to be that knight. A statue of Stuart by sculptor Frederick Moynihan was dedicated on Richmond's Monument Avenue at Stuart Circle in 1907. Like General Stonewall Jackson, his equestrian statue faces north, indicating that he died in the war. In 1884 the town of Taylorsville, Virginia, was renamed Stuart. The British Army named two models of American-made World War II tanks, the M3 and M5, the Stuart tank in General Stuart's honor. A high school on Munson's Hill in Falls Church, Virginia, opened in 1959, [82] and a middle school in Jacksonville, Florida are named for him. [83] In early 2017, Fairfax County Public Schools established an Ad Hoc Working Committee to assist the Fairfax County School Board in determining whether to rename the Stuart High School in Virginia, in response to suggestions from students and local community members that FCPS should not continue to honor a Confederate General who fought in support of a cause dedicated to maintaining the institution of slavery in Virginia and other states. The creation of the committee followed the circulation of a petition started by actress Julianne Moore and Bruce Cohen in 2016, which garnered over 35,000 signatures in support of changing the school's name to one honoring the late United States Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall.[84] In July 27, the Fairfax County School Board approved a measure to change the school name no later than the start of the 2019 school year. The measure asks that "Stuart High School" be considered as a possibility for the new name. [82] On October 27, 2017, the Fairfax County School Board voted to change the name of J. Stuart High School to Justice High School.

Board member Sandy Evans from the Mason District said that the name will honor Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall, Barbara Rose Johns, Louis Gonzaga Mendez Jr. And all those who have fought for justice and equality.

Johns was a Civil Rights leader. Army officer who joined the Virginia education department and lived for many years in Falls Church. On June 12, 2018, students of the school were given the opportunity to narrow down the choices for renaming the school from seven to three. Northside Elementary received 190 votes, Barack Obama Elementary earned 166 votes, and Wishtree Elementary received 127 votes.

From there, the administration of Richmond Public Schools recommended to the school board that it rename the school after Barack Obama. Superintendent Jason Kamras said, It's incredibly powerful that in the capital of the Confederacy, where we had a school named for an individual who fought to maintain slavery, that now we're renaming that school after the first black president. A lot of our kids, and our kids at J.Stuart, see themselves in Barack Obama. The student population of the newly named Barack Obama Elementary School is made up of more than 90 percent African-Americans. [87] The 34-inch by 34-inch flag was hand-sewn for Stuart by Flora in 1862 and Stuart carried it into some of his most famous battles. Stuart Birthplace Preservation Trust, Inc.

In 1992 to preserve and interpret it. Route 58, in Virginia, is name the J.

Stuart statue on Monument Avenue, Richmond, VA, unveiled May 30, 1907. Another view of the J. Stuart statue on Monument Avenue in Richmond, Virginia. In the long-running comic book G.

Combat, featuring "The Haunted Tank", published by DC Comics from the 1960s through the late 1980s, the ghost of General Stuart guided a tank crew (the tank being, at first, a Stuart, later a Sherman) commanded by his namesake, Lt. Joseph Fuqua played Stuart in the films Gettysburg and Gods and Generals. Errol Flynn played Stuart in the movie Santa Fe Trail, depicting his antebellum life, confronting John Brown in Kansas and at Harper's Ferry. The movie has become infamous for its many historical inaccuracies, one of which was that Stuart, George Armstrong Custer (portrayed by Ronald Reagan in the film), and Philip Sheridan were firm friends and all attended West Point together in 1854. Jeb Stuart was evoked by G.

Joe character, Cross Country, in the third episode of the mini-series, "Arise Serpentor, Arise". Jeb Stuart is mentioned by the Baladeer in Season four, episode 10 of the TV Series, The Dukes of Hazzard. Stuart, along with his warhorse Skylark, is featured prominently in the novel Traveller by Richard Adams. In the alternate history novel Gray Victory (1988), author Robert Skimin depicts Stuart surviving his wound from the battle of Yellow Tavern.

After the war, in which the Confederacy emerges victorious, he faces a court of inquiry over his actions at the Battle of Gettysburg. In Harry Turtledove's 1992 alternate-history novel The Guns of the South, Stuart features as one of Lee's generals as the AWB bring back AK-47 rifles from 2014 to 1864. Men under Stuart's command are the first Confederate troops to use the AK-47 in battle. Stuart is so impressed with the new rifle that he sells his personal LeMat Revolver and replaces it with an AK-47. This is the first volume of the Southern Victory series, where the US and CSA fight each other repeatedly in the 19th and 20th centuries.Stuart's son and grandson also appear in these novels. Several short stories in Barry Hannah's collection Airships feature Stuart as a character. Stuart's route to Gettysburg is the impetus for the sci-fi-ish book An End to Bugling by Edmund G. Stuart is also a character in L.

Elliott's Annie, Between the States. Stuart is a character in the historical adventure novel Flashman and the Angel of the Lord by George MacDonald Fraser featuring Stuart's early-career role in the US Army at John Brown's raid on Harpers Ferry.

"When I Was On Horseback, " a song on the folk group Arborea's album Fortress of the Sun (2013), features lyrics that refer to Stuart's death near Richmond, Virginia. List of American Civil War generals (Confederate). The Maryland Campaignor Antietam Campaignoccurred September 420, 1862, during the American Civil War. Lee's first invasion of the North was repulsed by the Army of the Potomac under Maj.

McClellan, who moved to intercept Lee and his Army of Northern Virginia and eventually attacked it near Sharpsburg, Maryland. The resulting Battle of Antietam was the bloodiest single-day battle in American history. Following his victory in the Northern Virginia Campaign, Lee moved north with 55,000 men through the Shenandoah Valley starting on September 4, 1862.His objective was to resupply his army outside of the war-torn Virginia theater and to damage Northern morale in anticipation of the November elections. He undertook the risky maneuver of splitting his army so that he could continue north into Maryland while simultaneously capturing the Federal garrison and arsenal at Harpers Ferry.

McClellan accidentally found a copy of Lee's orders to his subordinate commanders and planned to isolate and defeat the separated portions of Lee's army. Stonewall Jackson surrounded, bombarded, and captured Harpers Ferry (September 1215), McClellan's army of 102,000 men attempted to move quickly through the South Mountain passes that separated him from Lee.

The Battle of South Mountain on September 14 delayed McClellan's advance and allowed Lee sufficient time to concentrate most of his army at Sharpsburg. The Battle of Antietam (or Sharpsburg) on September 17 was the bloodiest day in American military history with over 22,000 casualties. Lee, outnumbered two to one, moved his defensive forces to parry each offensive blow, but McClellan never deployed all of the reserves of his army to capitalize on localized successes and destroy the Confederates. On September 18, Lee ordered a withdrawal across the Potomac and on September 1920, fights by Lee's rear guard at Shepherdstown ended the campaign. Although Antietam was a tactical draw, it meant the strategy behind Lee's Maryland Campaign had failed. President Abraham Lincoln used this Union victory as the justification for announcing his Emancipation Proclamation, which effectively ended any threat of European support for the Confederacy. Main articles: Northern Virginia Campaign and Second Battle of Bull Run. Further information: Peninsula Campaign, Seven Days Battles, Eastern Theater of the American Civil War, and American Civil War. The year 1862 started out well for Union forces in the Eastern Theater. McClellan's Army of the Potomac had invaded the Virginia Peninsula during the Peninsula Campaign and by June stood only a few miles outside the Confederate capital at Richmond. Lee assumed command of the Army of Northern Virginia on June 1, 1862, fortunes reversed. Lee fought McClellan aggressively in the Seven Days Battles; McClellan lost his nerve, and his army retreated down the Peninsula. Lee then conducted the Northern Virginia Campaign in which he outmaneuvered and defeated Maj. John Pope and his Army of Virginia, most significantly at the Second Battle of Bull Run (Second Manassas). Lee's Maryland Campaign can be considered the concluding part of a logically connected, three-campaign, summer offensive against Federal forces in the Eastern Theater. The Confederates had suffered significant manpower losses in the wake of the summer campaigns. Nevertheless, Lee decided his army was ready for a great challenge: an invasion of the North. His goal was to reach the major Northern states of Maryland and Pennsylvania, and cut off the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad line that supplied Washington, D. His movements would threaten Washington and Baltimore, so as to annoy and harass the enemy. Several motives led to Lee's decision to launch an invasion. First, he needed to supply his army and knew the farms of the North had been untouched by war, unlike those in Virginia. Moving the war northward would relieve pressure on Virginia. Second was the issue of Northern morale. Lee knew the Confederacy did not have to win the war by defeating the North militarily; it merely needed to make the Northern populace and government unwilling to continue the fight. With the Congressional elections of 1862 approaching in November, Lee believed that an invading army playing havoc inside the North could tip the balance of Congress to the Democratic Party, which might force Abraham Lincoln to negotiate an end to the war.He told Confederate President Jefferson Davis in a letter of September 3 that the enemy was much weakened and demoralized. There were secondary reasons as well.

The Confederate invasion might be able to incite an uprising in Maryland, especially given that it was a slave-holding state and many of its citizens held a sympathetic stance toward the South. Some Confederate politicians, including Jefferson Davis, believed the prospect of foreign recognition for the Confederacy would be made stronger by a military victory on Northern soil, but there is no evidence that Lee thought the South should base its military plans on this possibility. Nevertheless, the news of the victory at Second Bull Run and the start of Lee's invasion caused considerable diplomatic activity between the Confederate States and France and the United Kingdom. McClellan, who had done it after the Union defeat at the First Battle of Bull Run (First Manassas).He knew that McClellan was a strong organizer and a skilled trainer of troops, able to recombine the units of Pope's army with the Army of the Potomac faster than anyone. On September 2, 1862, Lincoln named McClellan to command the fortifications of Washington, and all the troops for the defense of the capital. "[10] The appointment was controversial in the Cabinet, a majority of whom signed a petition declaring to the president "our deliberate opinion that, at this time, it is not safe to entrust to Major General McClellan the command of any Army of the United States. "[11] The president admitted that it was like "curing the bite with the hair of the dog. " But Lincoln told his secretary, John Hay, "We must use what tools we have.

There is no man in the Army who can man these fortifications and lick these troops of ours into shape half as well as he. If he can't fight himself, he excels in making others ready to fight. Further information: Antietam Union order of battle. McClellan's Army of the Potomac, bolstered by units absorbed from John Pope's Army of Virginia, included six infantry corps, about 102,000 men. The I Corps, under Maj.

Joseph Hooker, consisted of the divisions of Brig. The II Corps, under Maj. Sumner, consisted of the divisions of Maj.

Richardson and John Sedgwick, and Brig. The V Corps, under Maj. Fitz John Porter, consisted of the divisions of Maj. The VI Corps, under Maj. Franklin, consisted of the divisions of Maj.

"Baldy" Smith, and a division from the IV Corps under Maj. The IX Corps, under Maj. Burnside, consisted of the divisions of Brig. Rodman, and the Kanawha Division, under Brig. The XII Corps, under Maj.Mansfield, consisted of the divisions of Brig. Greene, and the cavalry division of Brig. During the march north into Maryland, McClellan changed his army's command structure, appointing commanders for three "wings": the left, commanded by William B.

Franklin, consisted of his own VI Corps plus the division of Darius Couch; the center, under Edwin Sumner, consisted of his II Corps and the XII Corps; the right, under Ambrose Burnside, consisted of his IX Corps temporarily commanded by Maj. Reno until he was killed at South Mountain and the I Corps. This wing organization was revoked just before the start of the Battle of Antietam.The army that McClellan took into Maryland was not an entirely cohesive or battle-ready fighting force. At its core were the Peninsula veterans of the II, V, and VI Corps, but a large portion of the army were untested rookie regiments or troops who had never fought as part of the Army of the Potomac. Some of the rookies had never even loaded their muskets, and others were unknowingly armed with defective weapons.

McClellan had quickly integrated John Pope's three corps into the main army; these were redesignated as the I, XI, and XII Corps. A number of new nine-month regiments were added to the army, including two entire new divisions commanded by Brig.

Gens William French and Andrew Humphreys. Pope had blamed Fitz-John Porter for the defeat at Second Bull Run and had him removed from command. McClellan quickly restored his friend Porter to command of the V Corps, but after the former was terminated from command in October, Porter lost his protector and found himself court-martialed. He spent much of his life trying to rehabilitate himself. Irvin McDowell, also blamed for Second Bull Run, was removed from command of the I Corps and replaced by Joe Hooker. Nathaniel Banks remained in command of the XII Corps until September 12, when he was fired. The III Corps and XI Corps had both suffered severe losses at Second Bull Run and were almost driven from the field in panic; they were left behind in Washington D.Of the six corps that participated in the Maryland Campaign, the II and VI were the largest and most well-rested as neither had fought since the Seven Days Battles over two months earlier (aside from one brigade of the VI Corps which had been attacked by the Confederates and routed while scouting near Bull Run). The II Corps received a new division of nine month troops commanded by Brig. Gen William French and the VI Corps had one new regiment, all the rest of the men in both corps had fought on the Peninsula. The I Corps was the smallest, as it had suffered heavy losses at Second Bull Run (one of its divisions had also been heavily engaged in the Seven Days) and would lose still more men at South Mountain; it's estimated that the corps had 8000 men at Antietam out of a paper strength of 14,000. The V Corps also consisted mostly of Peninsula veterans; Morell's division had suffered severe losses at Second Bull Run and had its ranks filled out with green troops.

A new division of nine-month regiments led by Brig. Humphreys was added, but they would not arrive until after Antietam.

The IX Corps had had two divisions at Second Bull Run (commanded by General Reno as Burnside was not present at the battle); for the Maryland Campaign, it was joined by a third division under Brig. Gen Samuel Sturgis and Brig. Gen Jacob Cox's "Kanawah" Division, on loan from the West Virginia area. It included several green regiments and the corps as a whole was quite inexperienced as Second Bull Run had been the only serious engagement it had fought in.

The XII Corps had not fought at Second Bull Run and its last engagement had been at Cedar Mountain a month earlier; some men from this corps were left in the Washington defenses and swapped for a number of green regiments. After Nathaniel Banks was fired on September 12, the senior division commander, Alpheus Williams, commanded the corps for a few days until Maj. Mansfield, an old regular army officer with 40 years of service, was named to command. Further information: Antietam Confederate order of battle. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia was organized into two large infantry corps, about 55,000 effectives at the beginning of September.

The First Corps, under Maj. James Longstreet, consisted of the divisions of Maj.John Bell Hood, and an independent brigade under Brig. The Second Corps, under Maj. "Stonewall" Jackson, consisted of the divisions of Brig. Hill (the Light Division), Brig. The remaining units were the Cavalry Corps, under Maj.

Stuart, and the reserve artillery, commanded by Brig. The Second Corps was organized with artillery attached to each division, in contrast to the First Corps, which reserved its artillery at the corps level. One of the more unusual aspects of the Maryland Campaign was the severely understrength condition of the Army of Northern Virginia.

Lee had commanded nearly 90,000 men in when he assumed command of the army in June 1862, but the Seven Days Battles cost him 20,000 casualties and the Northern Virginia Campaign another 12,000 or so. Along with the marching into Maryland, the manpower of the army dropped even more due to straggling, lack of food, and a significant number of soldiers in Virginia regiments deserting on the grounds that they had signed up to defend their state and not invade the North. Significant numbers of Confederate soldiers had no shoes and were unable to handle the macadamized roads of Maryland. Lee may have had under 40,000 men on the field at Antietam, the smallest and most ragged his army would be until the final days of the Petersburg Siege.Many brigades were the size of regiments, their regiments company-sized. Despite the ragged condition of the army, morale was high and almost all of the Confederate were veterans, which put them at an advantage over the numerous green Union regiments. The divisions of McLaws and D. Hill had been left in the Richmond area during the Northern Virginia Campaign; they quickly rejoined the army for the march into Maryland.

Lee was also reinforced by Brig. Walker's two-brigade division from North Carolina.The exact size of the Army of Northern Virginia at Antietam has been a source of debate since the 19th century; Lost Causers during the postwar years presented a picture of Lee being severely understrength and possibly having as few as 30,000 men on the field. Union generals and veterans of the war generally believed that the Army of Northern Virginia was not that small on September 17, and estimated Confederate strength as high as 50,000 men.

It seems almost certain that the most exhausted and understrength Confederate divisions were Lawton's and the Stonewall Division, as both had been fighting and marching without any letup for two months. Other Confederate divisions such as D. Hill's, had not fought since the Peninsula and would have been better rested and more physically fit. The lack of food was a serious problem for the Army of Northern Virginia, as most crops were a month away from harvesting in September and many soldiers were forced to subsist on field corn and green apples, which gave them indigestion and diarrhea. As noted above, malnutrition was greatest in the two divisions of Jackson's old Valley Army due to two months of unbroken fighting and marching. Maryland Campaign, actions September 315, 1862. Confederate troops marching south on N Market Street, Frederick, Maryland, during the Civil War. On September 3, just two days after the Battle of Chantilly, Lee wrote to President Davis that he had decided to cross into Maryland unless the president objected. On the same day, Lee began shifting his army north and west from Chantilly towards Leesburg, Virginia.On September 4, advance elements of the Army of Northern Virginia crossed into Maryland from Loudoun County. The main body of the army advanced into Frederick, Maryland, on September 7. The 55,000-man army had been reinforced by troops who had been defending Richmondthe divisions of Maj.

Hill and Lafayette McLaws and two brigades under Brig. Walkerbut they merely made up for the 9,000 men lost at Bull Run and Chantilly.

Lee's invasion coincided with another strategic offensive by the Confederacy. Generals Braxton Bragg and Edmund Kirby Smith had simultaneously launched invasions of Kentucky. [17] Jefferson Davis sent to all three generals a draft public proclamation, with blank spaces available for them to insert the name of whatever state their invading forces might reach. Davis wrote to explain to the public (and, indirectly, the European Powers) why the South seemed to be changing its strategy. Until this point, the Confederacy had claimed it was the victim of aggression and was merely defending itself against foreign invasion.Davis explained that the Confederacy was still waging a war of self-defense. He wrote there was "no design of conquest, " and that the invasions were only an aggressive effort to force the Lincoln government to let the South go in peace. We are driven to protect our own country by transferring the seat of war to that of an enemy who pursues us with a relentless and apparently aimless hostility.

Davis's draft proclamation did not reach his generals until after they had issued proclamations of their own. They stressed that they had come as liberators, not conquerors, to these border states, but they did not address the larger issue of the Confederate strategy shift as Davis had desired. Lee's proclamation announced to the people of Maryland that his army had come with the deepest sympathy [for] the wrongs that have been inflicted upon the citizens of the commonwealth allied to the States of the South by the strongest social, political, and commercial ties... To aid you in throwing off this foreign yoke, to enable you again to enjoy the inalienable rights of freemen. Lee divided his army into four parts as it moved into Maryland. After receiving intelligence of militia activity in Chambersburg, Pennsylvania, Lee sent Maj. James Longstreet to Boonsboro and then to Hagerstown. The intelligence overstated the threat since only 20 militiamen were in Chambersburg at the time. "Stonewall" Jackson was ordered to seize the Union arsenal at Harpers Ferry with three separate columns. This left only the thinly spread cavalry of Maj. Stuart and the division of Maj. Hill to guard the army's rear at South Mountain. The specific reason Lee chose this risky strategy of splitting his army to capture Harpers Ferry is not known. One possibility is that he knew it commanded his supply lines through the Shenandoah Valley. Before he entered Maryland he had assumed that the Federal garrisons at Winchester, Martinsburg, and Harpers Ferry would be cut off and abandoned without firing a shot (and, in fact, both Winchester and Martinsburg were evacuated). [22] Another possibility is that it was simply a tempting target with many vital supplies but virtually indefensible. [20] McClellan requested permission from Washington to evacuate Harpers Ferry and attach its garrison to his army, but his request was refused.Lee's invasion was fraught with difficulties from the beginning. The Confederate Army's numerical strength suffered in the wake of straggling and desertion. Although he started from Chantilly with 55,000 men, within 10 days this number had diminished to 45,000. [24] Some troops refused to cross the Potomac River because an invasion of Union territory violated their beliefs that they were fighting only to defend their states from Northern aggression. Countless others became ill with diarrhea after eating unripe "green corn" from the Maryland fields or fell out because their shoeless feet were bloodied on hard-surfaced Northern roads.

[22] Lee ordered his commanders to deal harshly with stragglers, whom he considered cowards "who desert their comrades in peril" and were therefore "unworthy members of an army that has immortalized itself" in its recent campaigns. Upon entering Maryland, the Confederates found little support; rather, they were met with reactions that ranged from a cool lack of enthusiasm, to, in most cases, open hostility. Lee was disappointed at the state's resistance, a condition that he had not anticipated.

Although Maryland was a slaveholding state, Confederate sympathies were considerably less pronounced among the lower and middle classes, which generally supported the Union cause, than among the pro-secession legislature, the majority of the members of which hailed from Southern Maryland, an area almost entirely economically dependent on slave labor. Furthermore, many of the fiercely pro-Southern Marylanders had already traveled south at the beginning of the war to join the Confederate Army in Virginia. Only a "few score" of men joined Lee's columns in Maryland. Maryland and Pennsylvania, alarmed and outraged by the invasion, rose at once to arms. Pennsylvania Governor Andrew Curtin called for 50,000 militia to turn out, and he nominated Maj. Reynolds, a native Pennsylvanian, to command them. This caused considerable frustration to McClellan and Reynolds's corps commander, Joseph Hooker, but general-in-chief Henry W.Halleck ordered Reynolds to serve under Curtin and told Hooker to find a new division commander. As far north as Wilkes-Barre, church and courthouse bells rang out, calling men to drill. In Maryland, panic was much more widespread than in Pennsylvania, which was not yet immediately threatened. Baltimore, which Lee incorrectly regarded as a hotbed of secession merely waiting for the appearance of Confederate armies to revolt, took up the war call against him immediately. When it was learned in Baltimore that Southern armies had crossed the Potomac, the reaction was one of instantaneous hysteria followed quickly by stoic resolution.

Crowds milled in the street outside newspaper offices waiting for the latest bulletins, and the sale of liquor was halted to restrain the excitable. The public stocked up on food and other essentials, fearing a siege. Philadelphia was also sent into a flurry of frenzied preparations, despite being over 150 miles (240 km) from Hagerstown and in no immediate danger.

I did not believe before coming here that there was so much Union feeling in the state. The whole population [of Frederick] seemed to turn out to welcome us.

When Genl McClellan came thro[ugh] the ladies nearly eat him up, they kissed his clothing, threw their arms around his horse's neck and committed all sorts of extravagances. McClellan moved out of Washington starting on September 7 with his 87,000-man army in a lethargic pursuit. [31] He was a naturally cautious general and assumed he would be facing over 120,000 Confederates. He also was maintaining running arguments with the government in Washington, demanding that the forces defending the capital city report to him.[32] The army started with relatively low morale, a consequence of its defeats on the Peninsula and at Second Bull Run, but upon crossing into Maryland, their spirits were boosted by the "friendly, almost tumultuous welcome" that they received from the citizens of the state. Although he was being pursued at a leisurely pace by Maj. McClellan and the Union Army of the Potomac, outnumbering him more than two to one, Lee chose the risky strategy of dividing his army to seize the prize of Harpers Ferry.

While the corps of Maj. James Longstreet drove north in the direction of Hagerstown, Lee sent columns of troops to converge and attack Harpers Ferry from three directions. The largest column, 11,500 men under Jackson, was to recross the Potomac and circle around to the west of Harpers Ferry and attack it from Bolivar Heights, while the other two columns, under Maj.Lafayette McLaws (8,000 men) and Brig. Walker (3,400), were to capture Maryland Heights and Loudoun Heights, commanding the town from the east and south. The Army of the Potomac reached Frederick, Maryland, on September 13. Barton Mitchell of the 27th Indiana Infantry discovered a mislaid copy of the detailed campaign plans of Lee's armySpecial Order 191wrapped around three cigars. The order indicated that Lee had divided his army and dispersed portions geographically, thus making each subject to isolation and defeat in detail.

Upon realizing the intelligence value of this discovery, McClellan threw up his arms and exclaimed, Now I know what to do! He waved the order at his old Army friend, Brig.

John Gibbon, and said, Here is a paper with which if I cannot whip Bobbie Lee, I will be willing to go home. I think Lee has made a gross mistake, and that he will be severely punished for it. I have all the plans of the rebels, and will catch them in their own trap if my men are equal to the emergency. McClellan waited 18 hours before deciding to take advantage of this intelligence.

His delay squandered the opportunity to destroy Lee's army. On the night of September 13, the Army of the Potomac moved toward South Mountain, with Burnside's right wing of the army directed to Turner's Gap, and Franklin's left wing to Crampton's Gap.

South Mountain is the name given to the continuation of the Blue Ridge Mountains after they enter Maryland. It is a natural obstacle that separates the Shenandoah Valley and Cumberland Valley from the eastern part of Maryland. Crossing the passes of South Mountain was the only way to reach Lee's army. Lee, seeing McClellan's uncharacteristic aggressive actions, and possibly learning through a Confederate sympathizer that his order had been compromised, [37] quickly moved to concentrate his army.

He chose not to abandon his invasion and return to Virginia yet, because Jackson had not completed the capture of Harpers Ferry. Instead, he chose to make a stand at Sharpsburg, Maryland. In the meantime, elements of the Army of Northern Virginia waited in defense of the passes of South Mountain. Battles of the Maryland Campaign. Further information: Battle of Harpers Ferry.

As Jackson's three columns approached Harpers Ferry, Col. Miles, Union commander of the garrison, insisted on keeping most of the troops near the town instead of taking up commanding positions on the surrounding heights. The South Carolinians under Brig. Kershaw encountered the slim defenses of the most important position, Maryland Heights, but only brief skirmishing ensued. Strong attacks by the brigades of Kershaw and William Barksdale on September 13 drove the mostly inexperienced Union troops from the heights.

During the fighting on Maryland Heights, the other Confederate columns arrived and were astonished to see that critical positions to the west and south of town were not defended. Jackson methodically positioned his artillery around Harpers Ferry and ordered Maj. Hill to move down the west bank of the Shenandoah River in preparation for a flank attack on the Federal left the next morning. By the morning of September 15, Jackson had positioned nearly 50 guns on Maryland Heights and at the base of Loudoun Heights. He began a fierce artillery barrage from all sides and ordered an infantry assault.

Miles realized that the situation was hopeless and agreed with his subordinates to raise the white flag of surrender. Before he could surrender personally, he was mortally wounded by an artillery shell and died the next day. Jackson took possession of Harpers Ferry and more than 12,000 Union prisoners, then led most of his men to join Lee at Sharpsburg, leaving Maj. Hill's division to complete the occupation of the town.

Further information: Battle of South Mountain and Battle of Crampton's Gap. US ARMY MARYLAND CAMPAIGN MAP 3 (SOUTH MOUNTAIN). Pitched battles were fought on September 14 for possession of the South Mountain passes: Crampton's, Turner's, and Fox's Gaps. Hill defended Turner's and Fox's Gaps against Burnside.

Lafayette McLaws defended Crampton's Gap against Franklin, who was able to break through at Crampton's Gap, but the Confederates were able to hold Turner's and Fox's, if only precariously. Lee realized the futility of his position against the numerically superior Union forces, and he ordered his troops to Sharpsburg. McClellan was then theoretically in a position to destroy Lee's army before it could concentrate.

McClellan's limited activity on September 15 after his victory at South Mountain, however, condemned the garrison at Harpers Ferry to capture and gave Lee time to unite his scattered divisions at Sharpsburg. Further information: Battle of Antietam. Battle of Antietam (Sharpsburg), September 17, 1862. On September 16, McClellan confronted Lee near Sharpsburg. Lee was defending a line to the west of Antietam Creek.

At dawn on September 17, Maj. Joseph Hooker's I Corps mounted a powerful assault on Lee's left flank that began the bloody battle.Attacks and counterattacks swept across the Miller Cornfield and the woods near the Dunker Church as Maj. Mansfield's XII Corps joined to reinforce Hooker. Union assaults against the Sunken Road ("Bloody Lane") by Maj.

Sumner's II Corps eventually pierced the Confederate center, but the Federal advantage was not pressed. In the afternoon, Burnside's IX Corps crossed a stone bridge over Antietam Creek and rolled up the Confederate right. At a crucial moment, A.

Hill's division arrived from Harpers Ferry and counterattacked, driving back Burnside's men and saving Lee's army from destruction. Although outnumbered two to one, Lee committed his entire force, while McClellan sent in only four of his six available corps. This enabled Lee to shift brigades across the battlefield and counter each individual Union assault.

During the night, both armies consolidated their lines. In spite of crippling casualtiesUnion 12,401, or 25%; Confederate 10,316, or 31%Lee continued to skirmish with McClellan throughout September 18, while transporting his wounded men south of the Potomac. McClellan did not renew the offensive.

After dark, Lee ordered the battered Army of Northern Virginia to withdraw across the Potomac into the Shenandoah Valley. Further information: Battle of Shepherdstown.On September 19, a detachment of Maj. Fitz John Porter's V Corps pushed across the river at Boteler's Ford, attacked the Confederate rear guard commanded by Brig. Pendleton, and captured four guns.

Early on September 20, Porter pushed elements of two divisions across the Potomac to establish a bridgehead. This rearguard action discouraged further Federal pursuit. Lee successfully withdrew across the Potomac, ending the Maryland Campaign and summer campaigning altogether. President Lincoln was disappointed in McClellan's performance.He believed that the general's cautious and poorly coordinated actions in the field had forced the battle to a draw rather than a crippling Confederate defeat. He was even more astonished that from September 17 to October 26, despite repeated entreaties from the War Department and the president, McClellan declined to pursue Lee across the Potomac, citing shortages of equipment and the fear of overextending his forces. Halleck wrote in his official report, The long inactivity of so large an army in the face of a defeated foe, and during the most favorable season for rapid movements and a vigorous campaign, was a matter of great disappointment and regret. [44] Lincoln relieved McClellan of his command of the Army of the Potomac on November 7, effectively ending the general's military career.

Burnside rose to command the Army of the Potomac. The Eastern Theater was relatively quiet until December, when Lee faced Burnside at the Battle of Fredericksburg. Although a tactical draw, the Battle of Antietam was a strategic victory for the Union.

It forced the end of Lee's strategic invasion of the North and gave Abraham Lincoln the victory he was awaiting before announcing the Emancipation Proclamation on September 22, which took effect on January 1, 1863. Although Lincoln had intended to do so earlier, he was advised by his Cabinet to make this announcement after a Union victory to avoid the perception that it was issued out of desperation. The Confederate reversal at Antietam also dissuaded the governments of France and Great Britain from recognizing the Confederacy.